The issue brief examines Russia’s sustained bombardment of Odessa, Ukraine’s largest Black Sea port, as part of a broader strategy to sever Kyiv’s maritime access and establish regional dominance. Historically a cosmopolitan hub, Odessa now embodies contested identities between Ukrainian decolonisation and Russian imperial legacy. Moscow’s actions reflect both great-power behaviour and fears of NATO encirclement, with the Black Sea designated a zone of “exclusive national interest” in Russian doctrine. Neutralising Odessa would cripple Ukraine’s trade, military logistics, and strategic relevance to NATO, while exacerbating global food insecurity given Ukraine’s grain exports. The brief situates Russia’s campaign within a realist framework, arguing it mirrors precedents set by Western interventions that eroded international legal norms.

Introduction

Over the last few weeks, Russian strikes on the southern Ukrainian region of Odessa have resulted in widespread power cuts and extensive destruction of the region’s maritime infrastructure. The attacks targeted energy facilities, industrial complexes, transportation nodes and other critical infrastructure across several regions of southern Ukraine, leaving much of Odessa, the country’s largest Black Sea port, without power, heat or water. It is estimated that the attacks in the second week of December 2025 alone caused more than one million people in Ukraine to lose access to electricity during the peak of the harsh winter. Russian President Vladimir Putin had earlier threatened to sever Ukraine’s access to the sea as retaliation for drone attacks on tankers of Moscow’s ‘shadow fleet’ operating in the Black Sea.[1]

The intensified aerial bombardment of Odessa reflects Russia’s sustained strategic interest in neutralising the port and the city’s economic and military utility and demonstrating the vulnerability of Ukraine’s maritime ‘lifeline’. Capture or degradation of this lifeline could fundamentally alter the conflict’s strategic calculus by rendering Ukraine landlocked and establishing Russia’s complete maritime dominance across the Northern Black Sea littoral. These actions are indicative of a geopolitical logic rooted in traditional great-power behaviour and highlight Moscow’s concerns about strategic encirclement. Additionally, these reflect the limitations of present international institutions, which lack the capability to comprehend the competing perspectives of major powers and are unable to provide acceptable alternatives.

A. Historical Context: A Cosmopolitan Port’s Imperial Legacy

Emergence of Odessa: Odessa’s history dates to late 18th century and was established as ‘Khadjibey’ city by Empress Catherine the Great of Russia in 1794 following the defeat of Ottomans in the Russo-Turkish War (1787-1792). Located near the mouths of near the mouths of four major European rivers – the Danube, Dniester, Dnieper, and Bug – Khadjibey (or Hacibey to the Ottomans) served as a military fortress for Turkish forces before falling under Russian control in 1789. The city was renamed after the classical Greek hero Odysseus and feminised to Odessa, probably in honour of Czarina Catherine.[2] Odessa operated as a free port with a large cosmopolitan population, shaped by Greek, Italian, German, Polish, Jewish, and Russian communities, and became the fourth-largest city of the Russian Empire. After the Crimean War (1853-1856), Odessa developed into Russia’s largest grain-exporting port, and by 1910, Russian wheat exports accounted for approximately 36.4 per cent of total world wheat exports.[3] Historian Boris Belge’s detailed archival research demonstrates that grain exports through Odessa did indeed constitute a critical source of imperial revenue and enabled Russia’s integration into the gold standard international monetary system.[4]

The Soviet Period: The Soviet period (1917–1991) witnessed systematic dismantling of Odessa’s cosmopolitan culture and its institutional bases and the imposition of a new Soviet Russian identity that privileged industrial labour and military utility over mercantile pluralism. By the 1930s, Stalin’s purges and collectivisation policies had devastated Odessa’s merchant class and traditional economic structures.[5] The city was occupied by Nazi Germany along with Romanian allies in October 1941 and the region was designated as ‘Transnistria’. Out of an estimated 80,000 to 90,000 Jewish residents at the onset of Second World War, only about 5,000 survived before the city’s 1944 Soviet liberation. In Russian history, the heroic defence of Odessa by the Soviet Army and the residents earned the city the sobriquet ‘Hero City of Odessa’ and the Order of Lenin and the Gold Star medal from the Soviet authorities.[6] The post-war Soviet reconstruction of Odessa transformed the city from a cosmopolitan commercial hub into a strategic military port and industrial centre serving the Soviet state and Eastern Bloc economies.[7] The Black Sea Fleet, established in Sevastopol (Crimea), made Odessa a secondary but significant naval logistics hub. The massive internal migration within the Soviet Union brought Russian-speaking settlers to Ukrainian industrial centres, and by the 1980s, Russian had become the primary language of commerce, administration, and public life in Odessa.

Redefining Odessa’s Historical Legacy: With the outbreak of the Russia-Ukraine conflict in 2022, the Ukrainian government and the Odessa City Council took significant steps to distance the city from its imperial heritage. Notably, they voted to remove the statue of Catherine the Great, a prominent symbol of Odessa’s Russian imperial past, and to rename streets throughout the city. These actions represented a deliberate process of decolonisation, reflected in Ukraine’s desire to break away from the city’s historical association with Russian past and to assert a new identity. In contrast to Ukrainian initiatives, President Vladimir Putin in his 2023 media conference conveyed his unequivocal stance on the city’s status. He stated, “Neither Crimea nor the Black Sea has any connection to Ukraine. Odessa is a Russian city.”[8] President Putin’s declaration underscores the deep-rooted contest over Odessa’s identity and its historical and geopolitical significance within the broader conflict. Russia’s persistent claim to the city reflects the ongoing struggle between narratives of decolonisation and imperial legacy.

Geo-Strategic Significance of Black Sea Region: The ongoing conflict between Russia and Ukraine has once again brought the Black Sea region into the spotlight, making it a focal point in global politics. This growing prominence stems from its strategic location, as the Black Sea serves as a vital link connecting Europe and Asia. The region plays a crucial role in fostering economic, commercial and socio-political ties with its neighbouring areas, including the Caucasus, the Caspian and the Balkans. This unique geographical position makes it of interest to many countries, including major powers. The Black Sea is essential to Russia as it provides access to warm waters, a critical feature absent from the country’s other maritime outlets. These waters do not freeze in winter, offering unrestricted access to major trade routes. Thus, Russia’s geographical position and its reliance on the Black Sea underscore the region’s strategic importance for regional stability and future developments. Kremlin has always actively pursued foreign policy strategies to maintain its influence in the Black Sea. As such, the outcome of the ongoing conflict will likely shape the future geopolitical order in the Black Sea region.[9]

B. Russian Security Perspectives and NATO Expansion

The Security Dilemma: American political scientist John J. Mearsheimer argues that NATO’s eastward expansion lies at the root of the Ukraine crisis, forming part of a broader Western strategy to integrate Ukraine into Euro-Atlantic structures and gradually out of ‘Russia’s orbit’. From Moscow’s perspective, as Mearsheimer argues, great powers are inherently “sensitive to potential threats near their home territory” and seek strategic depth to ensure regime survival.[10] It is therefore essential to analyse Russian strategic considerations concerning Ukraine and Odessa within the context of traditional great-power dynamics, specifically regarding buffer zones and spheres of influence. Rather than characterising Russia’s “special operation” in Ukraine as imperial nostalgia or solely as an extension of Putin’s Novorossiya (New Russia) ambitions, it may be prudent to incorporate the impact of NATO’s eastward expansion on Russia’s security calculations into the analysis.

Russia’s 1997 National Security Blueprint explicitly warned that “the prospect of NATO expansion to the East is unacceptable” to Moscow, a position reiterated in subsequent stated policy doctrines.[11] This concern reflects the deeply embedded threat perceptions of a nation shaped by significant historical and geographical occurrences. The experience of multiple defensive wars left Russia with an entrenched fear of being attacked yet again from the obstacle-free western direction.[12] Russian strategic culture, shaped by invasions from Napoleon, Kaiser Germany, and Hitler, has produced what scholars term a “critical defence zone” mentality.[13] Its apprehension toward NATO stems from its longstanding perception of it as a significant security threat, which have been further reinforced by the actions of this trans-Atlantic military alliance after the Cold War.[14] For instance, American diplomat-historian George Kennan in his 1997 New York Times article had warned about the NATO expansion and contended that “it would be the most fateful error of American policy in the entire post-Cold War era.” He predicted that it would weaken Russian reformers, embolden hardliners, undermine strategic arms agreements and inflame the nationalistic, anti-Western and militaristic tendencies in Russian administration.[15]

The Ukrainian Question and Buffer Zone Dynamics: Successive Russian leaderships has viewed the prospects of Ukraine’s NATO membership as an irrevocable shift in the balance of power and as the erosion of Russia’s status in the European security calculus. Ukraine’s integration within NATO would materially affect Russia’s security by bringing US-led NATO forces much closer to Saint Petersburg, thereby making it vulnerable and echoing historical Soviet concerns that led to the 1939 Finnish War.[16] Therefore, to safeguard its western frontiers, Russia aims to secure a ‘buffer zone’ that necessitates the creation of a safe distance between its borders and NATO territory.[17]

The Broken Promises Debate. Russian officials contend that Western leaders repeatedly assured Russian leadership from Mikhail Gorbachev onwards that NATO would not expand eastward following German reunification. While the historical record remains contested, former US Ambassador to the Soviet Union Jack Matlock supports these Russian assertions claiming that Washington provided “categorical assurances to Gorbachev that if a united Germany were able to stay in NATO, it would not be moved eastward.”[18] Recently declassified documents from the United States Archives also indicate that senior US and Western officials did give such assurances to Gorbachev and Yeltsin. However, some other officials contend that these statements concerned Germany specifically, not broader NATO expansion.

NATO’s Eastward Expansion & Russian Security: Despite 75 per cent of Russia’s population and 25 per cent of its territory being part of European peninsula, the US and the Western leaders have consistently refused to recognise Russia as a power with principal stakes in European security. In fact, Moscow’s desire to join NATO during Yeltsin and Putin’s first tenures was brushed aside by Washington. Kremlin’s repeated protests over NATO’s expansion were ignored while the alliance continued to include new members and build new military infrastructure on territories bordering Russia. Over the years, its membership increased from 14 in 1986 to 32 in 2025, reinforcing Russian perceptions of encirclement and betrayal and empowering hardliners within the Kremlin.

C. Russia’s Security Doctrine and Recent Military Operations

The Black Sea in Russian Doctrine: Russia’s Maritime Doctrine (updated in 2022) designated the Black Sea and the adjacent Sea of Azov “as critical areas of national interest.”[19] This elevated these zones from areas of strategic competition to near-exclusively Russian-controlled areas where external military presence is deemed unacceptable. This redesignation to elevate Black Sea to Russian national security centrality is further reinforced by its state policy “in the Field of Naval Activities up to 2030” (adopted in 2017) and the National Security Strategy (adopted on 31 December 2015 and updated on 02 July 2021), all emphasising the Black Sea’s centrality.[20]

Russia’s Black Sea Fleet, based in Sevastopol (Crimea), is historically linked to Catherine the Great’s imperial strategy and remains a potent symbol of Russia’s aspirations of reclaiming great-power status and project influence into the Mediterranean and the Middle East. Empress Catherine II established the fleet as part her broader strategy to challenge Ottoman Turkish hegemony in the Black Sea region following Russia’s annexation of Crimea. Ever since, the fleet has played a significant role for successive Russian rulers, including during the Russo-Turkish Wars, the Crimean War (1853–1856), 19th-century power competition with Britain in the Eastern Mediterranean, and during the Cold War. [21]

For the contemporary Russian leadership, the Black Sea Fleet represents a tangible expression of Russia’s reclaiming of great power status following the disintegration of the Soviet Union in the early 1990s. As Mahmutaj notes, the fleet’s operational capability and effectiveness depend on its bases, supply ports, and infrastructure throughout the region, thereby enhancing the importance of Odessa, which serves as a critical logistics hub.

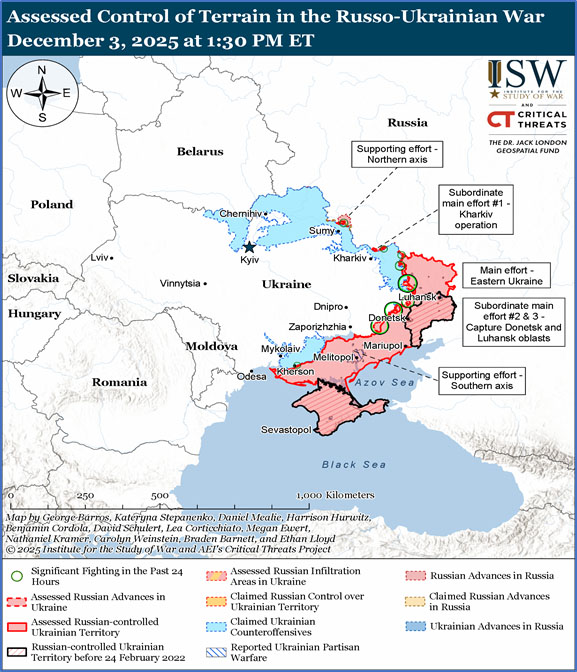

Recent Military Operations: Since December 2025, Russia has conducted a sustained aerial campaign against Odessa’s port infrastructure, energy grid, bridges, and transport arteries. Its ground forces remain concentrated far to the east conducting operations in the Pokrovsk-Dobropillya direction and the Hulyaipole sector in Zaporizhia Oblast.

Figure 1: Assessed Control of Terrain in Russia-Ukraine Conflict-December 2025

Russia achieved its most significant tactical success in the Odessa region in mid-November 2025 when its forces penetrated nearly 17 kilometres by crossing the Yanchur River near Uspenivka, North and Northeast of Hulyaipole. While it represented a critical breach of Ukrainian defences, these positions remain nearly 120 kilometres northeast of Odessa.[22]

Russia’s current operational approach exemplifies systematic degradation of Ukraine’s economic infrastructure to achieve political objectives without territorial occupation. This is demonstrated by its air strikes on power infrastructure and critical transportation nodes, including five attacks within 24 hours on Mayaky Bridge on 25 December 2025. The bridge, which is one of the two main crossings connecting southern Odesa to the rest of Ukraine, is crucial for supply routes to Danube ports, which are used for grain exports and military logistics, and, as Ukrainian Deputy Prime Minister Oleksii Kuleba warns, is responsible for 40 per cent of Ukraine’s fuel supplies.[23] This aligns with Russian military doctrine, which emphasises non-contact warfare, coercive bombardment, and the integration of kinetic and non-kinetic tools to achieve strategic outcomes at lower risks.[24]

From the Western perspective, Putin’s threats of December 2025 to “cut Ukraine off from the Black Sea” and repeated characterisations of Odessa as “Russian” serve multiple psychological purposes. It signals that Russian victory is inevitable and that Ukraine should capitulate on Moscow’s terms, legitimises the war domestically through historical narratives, and prepares discursive grounds for post-ceasefire territorial claims.[25] From Russia’s perspective, Odessa’s neutralisation through coercive bombardment helps it achieve economic attrition of Ukrainian resistance, demonstration of Russian capability despite naval setbacks, and psychological pressure on Ukrainian leadership.

D. Impact on Ukraine and Global Food Security

An Economic Calamity: For Ukraine, the potential loss or sustained degradation of Odessa would constitute an economic catastrophe. Approximately 70 per cent of all Ukrainian trade transits by sea, with Odessa accounting for nearly two-thirds (65 per cent) of that volume.[26] By some estimates, Russia’s targeted campaign has resulted in over $80 billion in losses to Ukraine’s agriculture sector since February 2022.[27] This strategy, if sustained over 18–24 months, could prove more effective than direct assault. By rendering Odessa’s ports non-functional and blockading maritime access, Moscow can deny Kyiv export revenue, degrade military supply capacity and create humanitarian crises that generate political pressure on the Ukrainian government to negotiate. Also, loss of Black Sea access eliminates Ukraine’s capacity for autonomous economic survival, rendering the state permanently dependent on the political goodwill of neighbours and Western powers. Alternate land routes through Poland, Romania and the Danube River can replace only about 10 to 15 per cent of normal maritime volumes, leaving a huge gap that will have a cascading effect on Ukrainian farmers who will be unable to export grain at competitive prices. This will weaken the rural economy, which accounts for a large share of Ukraine’s population and wealth, as farmers and rural services lose export income.

Degrading Ukraine’s Military Capability: Russian occupation or neutralisation of Odessa would eliminate Ukraine’s primary maritime gateway and cripple its ability to receive Western military assistance and fuel via sea routes, producing cumulative logistical collapse. Unlike tactical defeats, infrastructure destruction is difficult to reverse and steadily erodes combat effectiveness, morale and the state’s capacity to govern. As Russia continues to target logistics infrastructure such as the Mayaky Bridge, linking Ukraine with Moldova, and disrupt fuel and other critical supplies, it directly impacts Ukrainian war efforts. Ukrainian military analysis indicates that Russian strikes target “Ukraine’s main southern logistics routes” systematically degrading supply infrastructure in ways that compound over time.[28] Unlike discrete military defeats, which can be recovered through reinforcement and training, logistics degradation represents cumulative and difficult-to-reverse system failure. This would “not only undermine Ukraine’s economic viability but also diminish its broader strategic relevance”.[29]

Strategic Irrelevance: NATO’s interest in Ukrainian security derives substantially from Ukraine’s position as a buffer state on its eastern flank and as a potential member. However, the country stands to lose much of its strategic value to NATO if rendered landlocked, cut off from global trade, economically dependent on neighbouring states, and unable to project maritime power. It could be degraded to a level requiring permanent military and economic support without providing corresponding geopolitical benefits. This shift in strategic valuation would likely trigger reduced Western military support, as American and European resources are redirected towards more strategically beneficial commitments.[30]

Global Food Insecurity: Ukraine supplies one-sixth of global corn and one-eighth of global wheat, and any disruption carries profound implications for global food security, particularly for the developing world. [31] This is because Odessa Port remains the only Ukrainian port capable of handling Panamax-class vessels and large bulk carriers, with an annual total capacity of 40 million tonnes.[32]

E. Competing Geopolitical Visions

Russia’s strategy toward Odessa reflects the convergence of military pragmatism, long-term sustainability, great-power behaviour towards buffer zones, and an ideological conviction rooted in contested historical interpretation.[33] When viewed holistically, Moscow’s policy neither constitutes an isolated deviation from international legal norms nor reflects a unique rejection of the post-Cold War legal architecture. Rather, it reflects a systemic pattern of actions by the US-led Western military bloc over the last three and a half decades in which it has recurrently violated Article 2(4) of the UN Charter and fundamental principles of state sovereignty when their narrow strategic interests demanded it. From the US-led NATO bombing of Yugoslavia (1999) and Libya (2011) to the American invasion of Afghanistan (2001) and Iraq (2003) and the recent US regime change in Venezuela by abducting its sitting president, Nicolas Maduro, collectively reveals a systematic erosion of the legal constraints internationally, which are supposed to be binding on all states equally.

The Yugoslavia bombing was against a sovereign UN member state without Security Council Chapter VII authorisation. It posed no imminent threat to NATO states (no Article 51 was invoked) and, as per Robert Stannard, “NATO’s bombing constitutes use of force against territorial integrity... direct violation of Article 2(4).”[34] The 2003 Iraq invasion, premised on weapons of mass destruction, which could never be found, violated Article 2(4) as it was without Security Council authorisation. Bosen states, “the invasion established the principle that unilateral regime change conducted by sufficiently powerful states remained permissible despite Charter prohibitions.”[35] Libya 2011 demonstrated that Security Council authorisation could be interpreted expansively; Resolution 1973 authorised “all necessary measures” for civilian protection, yet was operationalised as a mandate for regime change and Gaddafi’s assassination.[36] In the recent military action to abduct Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro by the United States in early January 2026, even the pretence of legality was dispensed with. As Professor Habib Al Badawi of the Lebanese University asserts, the operation was carried out on the pretext of self-defence, without any International legal justification, Security Council authorisation or humanitarian emergency. It was conducted as a unilateral state action for purely geo-economic and geopolitical power assertion, undermining the jus ad bellum framework (the law governing the use of force).

Russia’s Ukraine campaign and Odessa operations could be viewed as logical augmentations of the precedents set by Western countries. Paradoxically, the legal frameworks invoked by Western states to condemn Russian actions and impose drastic sanctions are themselves violated by Western powers without comparable consequences. Russia operates within an explicitly realist framework: if powerful states violate the law when strategic interests demand, then Russia will do likewise—a logical deduction from observed Western behaviour.[37] The Odessa campaign specifically reflects Russia’s application of this realist logic to its maritime strategy. Its 2022 Maritime Doctrine designates the Black Sea-Sea of Azov basin as zones of “exclusive national interest,” language paralleling the US Monroe Doctrine.[38]

This perspective also aligns with traditional great power behaviour, that is , seeking buffer zones and influence over adjacent regions, though such behaviour conflicts with post-Cold War norms emphasising sovereignty and self-determination.[39] According to Russia’s UN Security Council Secretary Nikolai Patrushev, NATO’s expansion is perceived in Russia as an offensive military action aimed at achieving the larger objective of dismantling Russia’s political regime and system of values.

According to International Law, Russian actions are violative of fundamental principles of sovereignty, a dichotomy to Moscow’s security concerns which is an extension of protecting its own sovereignty. One of the binding international instruments was the Budapest Memorandum of 1994 where Russia assured Ukraine’s territorial integrity in exchange for nuclear weapons arsenal. This memorandum creates moral and legal obligations on Russia and highlights its violations. This is a classic case of conflict between great power geopolitics and the post-Cold War security architecture. A balanced analysis recognises both Russia’s predictable actions as a great power and the legitimate desire of small states for security alliances. The fundamental issue is that the current international institutions are neither able to comprehend competing perspectives nor to provide acceptable alternatives.

Conclusion

The significance of the Odessa Operations lies in the maturing of the pattern of violation of International Laws by major powers and in the inability of institutions designed post-Second World War to address competing visions. Today, all the major powers, that is, the US, Russia, China and some emerging powers, operate under the uninhibited assumption that the legitimate use of military force to achieve strategic objectives is permitted wherever political circumstances permit. International law or the rubric of the Rules-based International Order has become rhetorical device deployed to delegitimise rivals’ actions while justifying one’s own, all the while lacking the constraining capacity. The universal application of international laws, as espoused in the post-1945 international legal architecture, has been replaced by a de facto hierarchy in which major powers operate under different rules than lesser powers.

Resolution of the current crisis demands either broad reforms that enforce International Law equally, or a recognition that these laws functions as tools of power politics dressed in legal language. The Odessa operation, despite its severe consequences on the world stage, is once again illustrative of the limited consequences for such violations. It may encourage other nations to follow suit, undermining the role of law in global affairs. The result is not a temporary disruption but a shift towards an order in which international norms and laws retreat and power advances as the governing principle.

* Maj. Gen. Deepak Mehra (Kirti Chakra, AVSM, VSM) is an Indian Army veteran and former Indian Military Attaché in the Embassy of India, Moscow. An accomplished scholar, he specialises in Geopolitics with a focus on Russian Studies and is currently pursuing his PhD in the field, further enriching his depth of knowledge and global perspective. He is the Founding Director and CEO of ThorSec Global. He can be reached at deepakmehra67@yahoo.co.uk and deepak.mehra@thorsecglobal.com The views expressed are his own.

Bibliography:

Al Jazeera. “Russia-Ukraine War: The Battle for Odessa.” 9 March 2022. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/3/9/russia-ukraine-war-the-battle-for-Odessa.

Al Jazeera. “Why Is Russia Escalating Attacks on Ukraine’s Odessa?” 23 December, 2025. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2025/12/23/why-is-russia-escalating-attacks-on-ukraines-Odessa.

Basrur, Rajesh M. “India as a Regional Power: What Kind of Hegemon?” India Review(2017): 167–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/14736489.2017.1301299

Belge, B. “Railway, Steamships and Trade in the Port of Odessa, 1865–1914.” Journal of Balkan and Black Sea Studies(2020): 45–68.

Buzynski, I. “A Brief History of Odessa.” 2018. https://scalar.usc.edu/works/odessa/a-brief-history-of-odessa.

Center for Strategic and International Studies. “Setting the Record Straight on Ukraine’s Grain Exports.” 15 October, 2024. https://www.csis.org/analysis/setting-record-straight-ukraines-grain-exports.

Charap, Samuel, and Timothy J. Colton. Everyone Loses: The Ukraine Crisis and the Ruinous Contest for Post-Soviet Eurasia. New York: Routledge, 2018.

Chatham House. “Understanding Russia’s Black Sea Strategy.” 28 July, 2025. Royal Institute of International Affairs. https://www.chathamhouse.org/2025/07/understanding-russias-black-sea-strategy.

CIAO Strategic Analysis. “NATO Eastward Expansion and Russian Security.” 1997. Columbia International Affairs Online. https://ciaotest.cc.columbia.edu/olj/sa/sa_98meo02.html.

Foreign Policy. “Russia Sets Its Sights on Ukraine’s Biggest Port City.” 20 July 2022. https://foreignpolicy.com/2022/07/20/russia-ukraine-war-Odessa-black-sea/.

Institute for the Study of War. “Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, 3 December 2025.” 3 December, 2025. https://www.criticalthreats.org/analysis/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-december-3-2025.

Kennan, George F. “A Fateful Error.” The New York Times, 5 February 1997.

Kollakowski, Thomas. “Interpreting Russian Aims to Control the Black Sea Region Through Naval Geostrategy (Part One): ‘The Azov-Black Sea Basin as a Whole [...] This Is, in Fact, a Zone of Our Strategic Interests.’” The Journal of Slavic Military Studies 36, no. 1 (2023): 57–72. https://doi.org/10.1080/13518046.2023.2201112.

Mahmutaj, N. “The New Geopolitical Order in the Black Sea: Russia’s Role in the Area.” Connections QJ 22, no. 3 (2023): 45–58. https://doi.org/10.11610/Connections.22.3.06.

Mearsheimer, John J. “Why the Ukraine Crisis Is the West’s Fault: The Liberal Delusions That Provoked Putin.” Foreign Affairs 93, no. 5 (2014): 77–89.

Moscow Times. “Putin Says Ukraine’s Odessa Is Historically Russian. Reality Is More Complicated.” 11 January 2024.

Reuters. “Escalating Russian Airstrikes Aim to Cut Ukraine Off from Sea, Zelenskiy Says.” 20 December, 2025. https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/russia-hits-ports-bridge-escalating-strikes-ukraines-Odessa-region-2025-12-20/.

Reuters. “Putin Threatens to Cut Ukraine Off from Sea After Attacks on Tankers.” 2 December 2025. https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/putin-threatens-cut-ukraine-off-sea-after-attacks-tankers-2025-12-02/.

Russian Federation (Kremlin). “Concept of National Security of the Russian Federation.” 1997. Presidential Library, Russia. https://www.prlib.ru/en/node/354146.

Russian Federation (Kremlin). “Russian Maritime Doctrine.” 2022. http://static.kremlin.ru/media/events/files/ru/xBBH7DL0RicfdtdWPol32UekiLMTAycW.pdf.

Sabanadze, Natia, and Galip Dalay. “Understanding Russia’s Black Sea Strategy.” Chatham House Report, July 2025. https://www.chathamhouse.org/sites/default/files/2025-07/2025-07-28-russias-black-sea-strategy-sabanadze-dalay.pdf.

The Left Chapter. “Odessa: Hero City of the USSR.” Accessed on 28 December 2025 https://www.theleftchapter.com/post/odessa-hero-city-of-the-ussr.

Trachtenberg, Marc. “Putin’s Preventive War: The 2022 Invasion of Ukraine.” International Security 49, no. 3 (2025): 7–49. https://doi.org/10.1162/isec_a_00485.

Tsygankov, Andrei P. “The Sources of Russia’s Fear of NATO.” Communist and Post-Communist Studies 51, no. 2 (2018): 101–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.postcomstud.2018.04.002.

Wikipedia. “Odessa.” Accessed on 28 December 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Odessa.

Wilson Center. “Odessa: The Ukrainian Port That Inspired Big Dreams.” Accessed on 28 December 2025. https://www.wilsoncenter.org/blog-post/odessa-ukrainian-port-inspired-big-dreams.

Wohlforth, William C. “Russia.” In China’s Ascent: Power, Security, and the Future of International Politics, edited by Robert S. Ross and Zhu Feng, 162–87. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2006.

Zhurnal Mezhdunarodnaya Zhizn’. “Putin: ‘Odessa Is a Russian City’” 20 December 2023.

[1] Reuters, “Putin Threatens to Cut Ukraine Off from Sea After Attacks on Tankers,” December 2, 2025, https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/putin-threatens-cut-ukraine-off-sea-after-attacks-tankers-2025-12-02/.

[2] Wilson Center, “Odessa: The Ukrainian Port That Inspired Big Dreams,” accessed on 25 December 2025, https://www.wilsoncenter.org/blog-post/odessa-ukrainian-port-inspired-big-dreams.

[3] Wikipedia, “Odessa,” accessed on 25 December 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Odessa.

[4] B. Belge, “Railway, Steamships and Trade in the Port of Odessa, 1865–1914,” Journal of Balkan and Black Sea Studies (2020): 45–68.

[5] I. Buzynski, “A Brief History of Odessa,” 2018, https://scalar.usc.edu/works/odessa/a-brief-history-of-odessa

[6] The Left Chapter, “Odessa: Hero City of the USSR,” accessed on 25 December 2025, https://www.theleftchapter.com/post/odessa-hero-city-of-the-ussr

[7] N. Mahmutaj, “The New Geopolitical Order in the Black Sea: Russia's Role in the Area,” Connections QJ 22, no. 3 (2023): 45–58, https://doi.org/10.11610/Connections.22.3.06

[8]Zhurnal Mezhdunarodnaya Zhizn', “Putin: 'Odessa Is a Russian City,'“ December 20, 2023, https://en.interaffairs.ru/article/putin-odessa-is-a-russian-city

[9] Mahmutaj, “The New Geopolitical Order in the Black Sea,” 45–58

[10] John J. Mearsheimer, “Why the Ukraine Crisis Is the West's Fault: The Liberal Delusions That Provoked Putin,” Foreign Affairs 93, no. 5 (2014): 77–89.

[11] Russian Federation, “Concept of National Security of the Russian Federation,” 1997, Presidential Library, Russia, https://www.prlib.ru/en/node/354146

[12] William C. Wohlforth, “Russia,” in China's Ascent: Power, Security, and the Future of International Politics, ed. Robert S. Ross and Zhu Feng (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2006), 162–87.

[13] Marc Trachtenberg, “Putin's Preventive War: The 2022 Invasion of Ukraine,” International Security 49, no. 3 (2025): 7–49, https://doi.org/10.1162/isec_a_00485

[14] Andrei P. Tsygankov, “The Sources of Russia's Fear of NATO,” Communist and Post-Communist Studies 51, no. 2 (2018): 101–11, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.postcomstud.2018.04.002

[15] George F. Kennan, “A Fateful Error,” The New York Times, February 5, 1997

[16] Trachtenberg, “Putin's Preventive War,” 7–49

[17] Samuel Charap and Timothy J. Colton, Everyone Loses: The Ukraine Crisis and the Ruinous Contest for Post-Soviet Eurasia (New York: Routledge, 2018), 24–25

[18] CIAO Strategic Analysis, “NATO Eastward Expansion and Russian Security,” 1997, Columbia International Affairs Online, https://ciaotest.cc.columbia.edu/olj/sa/sa_98meo02.html

[19] Russian Federation, “Russian Maritime Doctrine,” 2022, http://static.kremlin.ru/media/events/files/ru/xBBH7DL0RicfdtdWPol32UekiLMTAycW.pdf

[20] Mahmutaj, “The New Geopolitical Order in the Black Sea,” 45–58

[21] Natia Sabanadze and Galip Dalay, “Understanding Russia's Black Sea Strategy,” Chatham House Report, July 2025, https://www.chathamhouse.org/sites/default/files/2025-07/2025-07-28-russias-black-sea-strategy-sabanadze-dalay.pdf

[22] Institute for the Study of War, “Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, December 3, 2025,” December 3, 2025, https://www.criticalthreats.org/analysis/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-december-3-2025

[23] Reuters, “Escalating Russian Airstrikes Aim to Cut Ukraine Off from Sea, Zelenskiy Says,” December 20, 2025, https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/russia-hits-ports-bridge-escalating-strikes-ukraines-Odessa-region-2025-12-20/

[24] Thomas Kollakowski, “Interpreting Russian Aims to Control the Black Sea Region Through Naval Geostrategy (Part One): 'The Azov-Black Sea Basin as a Whole [...] This Is, in Fact, a Zone of Our Strategic Interests,'“ The Journal of Slavic Military Studies 36, no. 1 (2023): 57–72, https://doi.org/10.1080/13518046.2023.2201112

[25]Moscow Times, “Putin Says Ukraine's Odessa Is Historically Russian. Reality Is More Complicated,” January 11, 2024

[26] Al Jazeera, “Russia-Ukraine War: The Battle for Odessa,” March 9, 2022, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/3/9/russia-ukraine-war-the-battle-for-Odessa

[27] Center for Strategic and International Studies, “Setting the Record Straight on Ukraine's Grain Exports,” October 15, 2024, https://www.csis.org/analysis/setting-record-straight-ukraines-grain-exports

[28] Al Jazeera, “Why Is Russia Escalating Attacks on Ukraine's Odessa?,” December 23, 2025, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2025/12/23/why-is-russia-escalating-attacks-on-ukraines-Odessa

[29] Chatham House, “Understanding Russia's Black Sea Strategy,” July 28, 2025, Royal Institute of International Affairs, https://www.chathamhouse.org/2025/07/understanding-russias-black-sea-strategy

[30] Sabanadze and Dalay, “Understanding Russia's Black Sea Strategy.”

[31]Foreign Policy, “Russia Sets Its Sights on Ukraine's Biggest Port City,” July 20, 2022, https://foreignpolicy.com/2022/07/20/russia-ukraine-war-Odessa-black-sea/

[32] Wikipedia, “Odessa.”

[33] Tsygankov, ”The Sources of Russia's Fear of NATO.” 101–11

[34] Robert W. Stannard, “The Laws of War: An Examination of the Legality of NATO's Intervention in the Former Yugoslavia and the Role of the European Court of Human Rights in Redressing Claims for Civilian Casualties in War,” *Georgia Journal of International and Comparative Law 30, no. 3 (2002): 617–664 at https://digitalcommons.law.uga.edu/gjicl/vol30/iss3/11.

[35] Barry R. Posen, “Putin's Preventive War: The 2022 Invasion of Ukraine,” *International Security* 49, no. 3 (Winter 2024/2025): 7–49, https://doi.org/10.1162/isec_a_00501.

[36] Kuperman, A. J. (2013). A model humanitarian intervention? Reassessing NATO’s Libya Campaign, 38(1), 105–136. https://doi.org/10.1162/ISEC_a_00124

[37] Tsygankov, ”The Sources of Russia's Fear of NATO.” 101–11

[38]Russian Federation. (2022). Maritime doctrine of the Russian Federation. President of Russia (Kremlin). at http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/69192.

[39] Mearsheimer, ”Why the Ukraine Crisis Is the West's Fault: The Liberal Delusions That Provoked Putin”, 77–89