On 15 August this year, the Taliban completed three years of their rule after taking over Afghanistan in August 2021. To celebrate the day, they organised parades at various places across the country on 14 August and displayed their military power by showcasing mainly the weapons and armed vehicles that were left behind by the fleeing America led forces. These parades implied that the Taliban have been able to bring political stability to the country without any visible threat to their authority. The ruling regime is overwhelmingly Pashtun in the nature and character even if it has allowed nominal yet symbolic representation from various ethnic groups of Afghanistan.

In all this, one issue that has remained unaddressed is the issue of the rights of the Afghan women, who have been at the receiving end of the harsh policies rolled out by the Taliban since their takeover. Despite a lot of talking about women rights by the United Nations (UN) and the international community, the condition of women remains precarious. As 20-year-old Madina, a former university student said, “Three years have passed since the dreams of girls have been buried”.1

Ineffective measures (?)

In order to address the humanitarian situation in Afghanistan under Taliban rule, the UN has undertaken the initiative to host a series of meetings involving the Member State envoys and other stakeholders since May 2023 in Doha, Qatar. The first meeting had a focus on humanitarian aid and the overall stability of Afghanistan and did not include the Taliban. Various ways to support the Afghan people amidst the ongoing crisis were discussed by the international stakeholders.

The second meeting was held in February 2024. The Taliban were invited and set unacceptable conditions to attend it. In fact, they demanded that2 Afghan civil society members be excluded from the talks and they be treated as the country’s legitimate rulers. When their demands were not met, they skipped the event. The discussions in the second meeting continued to revolve around humanitarian assistance, women’s rights, and the need for political stability. There was an emphasis on engaging the Taliban without legitimising it.

In continuation of its efforts, the UN held the third meeting was held on 30 June-1 July 2024. The Taliban attended the meeting for the first time only after the UN decided not to include Afghan women in the discussions. The agenda in the third Doha meeting included integrating Afghanistan into the international community, addressing financial and banking restrictions, and tackling the country’s drug problem. The Taliban sought the release of $7 billion in frozen central bank reserves and discussed alternative livelihoods for farmers affected by the opium ban.

Interestingly, the UN along with some other countries are frequently criticized for engaging the Taliban and failing to make the Taliban authorities accountable for human rights violations in general and the rights of women in particular. The UN decision to exclude the women from attending the third meeting, which might have been a symbolic move to engage the Taliban and ensure their participation, drew natural criticism from the media. The UN special envoy, former Kyrgyz President Roza Otunbayeva, defended the UN stand by saying that women rights would be discussed in the meeting.3 Such concessions are perhaps being regarded as inconsequential and desirable, and as a way forward to bring the Taliban to the table. There is a view, however, that given the approach of the Taliban towards the women and minorities, such engagement is not going to moderate their views anytime soon.

While such arguments and expression of concerns are valid, without engaging the Taliban authorities it becomes almost impossible to seek the desired goals, unless there is yet another effort to attempt a regime change, for which there is no appetite whatsoever in the international community today, especially after concerted efforts to rebuild Afghanistan over almost two decades did not yield much dividend in the war-torn country.

As it is observed now, the UN does not consider engagement with the Taliban as “legitimization or normalization”4 of their regime per se and takes it as an engagement to find a way to protect the women and minorities along with the rights of the common Afghans. The question, therefore, should not be about the engagement but about the nature of the engagement and how to design it. The approach so far does not seem to have served the purpose.

Taliban’s unchanged approach towards women

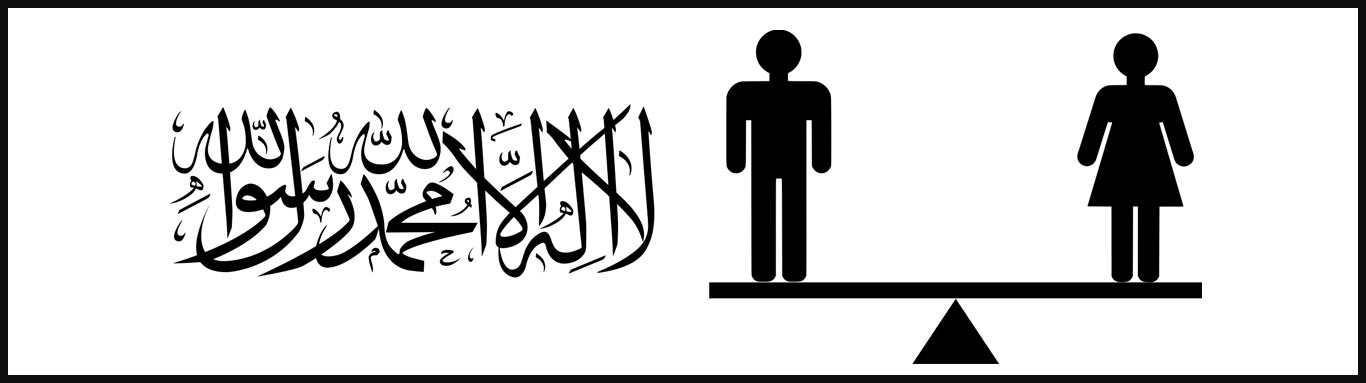

Ahead of the third Doha meeting, Zabihullah Mujahid, spokesperson of the Taliban regime had said that the Taliban “acknowledge [that] women are facing issues, but they are internal Afghan matters and need to be addressed locally within the framework of Islamic Sharia.”5 Much before Mujahid’s statement, the emir of the group, Haibatullah Akhundzada, speaking for the first time on the issue after Taliban returned to Kabul, had announced that the Taliban would reinforce harsh punishments of flogging and stoning, especially against women convicted of moral crimes, like adultery. He had claimed in his statement that women rights as advocated by the international community go against Islamic Sharia and the Taliban regime in Afghanistan will continue fighting against Western liberal democratic values. The emir had also asked: “Do [Afghan] women want the rights that Westerners are talking about? They are against Sharia and opinion of the clerics, who toppled Western democracy.”6

The above statement underlines two crucial points: one that the Taliban in their new avatar (Taliban 2.0) have not changed too much in their character from the Taliban 1.0, as some had expected; second that the Taliban regime has not shown any flexibility despite remaining unrecognised by the international community for the last three years. All this imply that efforts of the international organizations and the engagement heretofore have not induced any change in the Taliban behaviour.

Taliban and the politics of rights

Why are the Taliban ready to incur heavy costs but not let women and minorities in Afghanistan to exercise their inalienable rights? While they faced least resistance while taking control of Afghanistan from the previous administration in Kabul, the only section of the society that showed (and have consistently shown) some amount of resistance are the women groups who have been protesting against the Taliban policies ever since they came to power. They have a lot at stake. It is also true, if the women of the Afghan society are free and educated, they can help the Taliban in providing governance, running the country efficiently, or even get international legitimacy.

Why do the Taliban then deny rights to women, a policy that does not serve economically or help them politically?

The issue lies in the problematic interpretation of Islam by the Taliban who often mix it up with the culture of the Pashtuns while making tall claims that their policies represent “true Islam”. The phrase itself remains open to debates and contestations7 as there have been hundreds of Islamic scholars who have supported women rights. Even in his statement, Akhundzada said that the “opinion” of the clerics who defeated the West is that the latter’s understanding of human rights is different from the views of the Taliban/clergy. Why is the “opinion” of the Taliban clergy being preferred over the ‘opinion” of other clerics of Islam? The answer to the question lies in local politics.

Born out of an Islamist movement in early 1990s and greatly influenced by Deobandi Islam, the Taliban are predominantly from the Pashtun tribe, who interpret Islam from their cultural vantage point that generally prefers having women at home and not letting them be part of the public sphere. Before the Taliban came to power in 1996, women accounted for more than 50 percent of the students at Kabul University, 70 percent of school teachers, 50 percent of civilian government workers and 40 percent of the doctors, according to the Feminist Majority Foundation.8 Simi Wali, an Afghan woman activist fighting for women rights had talked about “gender apartheid gripping Afghanistan” way back in 1999, and had also urged the US to encourage active participation of women in the peace negotiations.9

The situation remains as disadvantageous for women even after a quarter of a century in Afghanistan rendering the efforts aimed at democratisation of Afghanistan by the international community futile. The systematic discrimination against women practised by the Taliban today points to the sad reality of continuing ‘gender apartheid’ in the country. The Taliban regime in power at the moment continues to rationalise its position by exploiting selective regressive interpretation of women rights contrasting it with women liberty championed by the West, which is deemed by them licentious and un-Islamic, in the backdrop of limited resources with which they are operating at the moment, due to sanctions by Western countries on their regime. The anti-West orientation of the Taliban regime indirectly legitimises their orthodox Islamist views, which are regarded as an anti-dote to the unwelcome and unrestrained liberalism of the West.

Soon after returning to power after the US withdrawal from Afghanistan, it was a surprise to hear from the Taliban that they would allow women to study and work. The Taliban leaders had made such commitments during the negotiations in Doha as well. However, when the time came to put such commitments to practice, the Taliban chose to evade their pledges. They were not happy to see that the Afghan women had been empowered and could deal with them directly. They sensed a threat: educated women could become part of civil society and participate in the debates and discussions related to the state at large. They also apprehended that given a chance, the women would demand right to work and question the patriarchal nature of the polity under the Taliban regime.

For the Taliban, possible consequences of the policy to let women have education and then work are that educated women would demand equal rights for women and equal say in decision making. Thus, in March 2022 it was decreed by the Taliban that girls would not be allowed to continue education after sixth grade, forcing more than 1.4 million Afghan girls out of schools. Then came the decision to keep them out of work.

Human rights and Afghan women

The US intervention in Afghanistan meant some relief from the restrictions imposed on them by the Taliban. In 2001, the Ministry of Women’s Affairs was established for promoting women’s rights and empowerment. In the new constitution that was adopted in 2004, 25 percent of parliamentary and provincial council seats as well as 30 percent of civil service positions were reserved for women.

Consequently, millions of girls who were denied education under the Taliban rule, were able to go to schools and receive education. The trend had started bearing fruits also, as many women were seen becoming part of the public services, working in the NGOs and other sectors of the Afghan economy. They, thus, had started contributing to the country’s political system as well as economy by serving as diplomats, ambassadors, journalists and cabinet ministers among others. Despite the fact that such measures remained limited and later got marred due to the half-hearted approach of the Hamid Karzai and Ashraf Ghani regimes and later massive corruption, they were a good beginning given the fact that these changes were brought about in a society that had had no such precedent.

Once the resurgent Taliban asserted itself and the West started showing signs of fatigue and announced its withdrawal from the country, the issue of women rights became a secondary issue: it was no longer as important an issue as it was in the beginning of the republic. It was raised by the weakening Kabul administration or some international players; for the Taliban it did not matter. Even during signing the deal with the Taliban in Doha in 2020, the US was more concerned about withdrawing from the country than ensuring that women and minority rights were protected under any future Taliban regime, although it is true that they built these issues into the Doha agreement as an important condition, based on which the Taliban have not been recognised by any country to this date.

Within weeks of their taking over, the Taliban announced an interim government which belied the hopes of an inclusive government. In yet another troubling sign, the Taliban replaced the Ministry of Women's Affairs with the ministry of Vice and Virtue in September of 2021 with a motive to take back whatever little agency women had acquired.10 In this context, the latest regressive statement by Zabihullah Mujahid on the issue of women rights that the women have been put in the same position where they were two decades back, proves that in terms of their approach to women, the Taliban are determined to cling on to an orthodox version of Islam which does not consider women as equal to men in society.

What may work?

Punitive policies like continuing to withhold recognition of the Taliban by the international community have not so far been effective in changing the Taliban behaviour. It might have built some pressure initially, but that has been defused by developments in the meanwhile following some countries making efforts to normalise their relationship with the Taliban regime and accommodate it. Few countries are even maintaining unofficial relations, have opened their embassies in Afghanistan and allowed the Taliban to maintain the Afghan embassies overseas. These countries want to protect their interests by engaging the Taliban and ensure that the latter would not let Afghan territory be used against them. But such measures are helping the Taliban to withstand and survive international pressure, making it difficult on the part of the international community to address the issue of women and minority rights.

More importantly, as the latest UN report shows, the Taliban have not been able to stop various terrorist groups operating from the Afghan territory.11 There is another view that in order to reform the Taliban, the global community should normalise interaction with them and persuade them to honour their commitments made in Doha in February 2020. The experience of past three years, however, proves otherwise. The Taliban have learnt that the world is tired of intervening in Afghanistan and there is no alternative for the international community other than cultivating them and work through them. They have, in a way, exposed the commitment of the US and its allies to women and human rights and are taking full advantage of the renewed apathy if not indifference of the international community towards Afghans in general and Afghan women in particular.

It may appear normal to many, but the international community cannot afford to turn a blind eye to the plight of women and other human rights violations under the Taliban regime. Various international forums need to actively raise these issues repeatedly with the Taliban and convey that any substantial aid or engagement would be after the Taliban would ensure women and minority rights. One way of going about it would be engaging various women groups in Afghanistan directly and empowering them by funding through their agencies. The UN missed an opportunity in the Doha meeting this time: it could have invited and facilitated various women representatives from Afghanistan to participate in the meeting to discuss various possible ways of engaging women in matters concerning the future of Afghanistan. While there was a view that it would have derailed the talks and hindered progress on the diplomatic front, a stalemated Doha dialogue would have been better than inviting the Taliban to have a monopoly rule in Kabul excluding a liberal elite that the West had enabled over almost two decades spending trillions of dollars.

There are many in Afghanistan today who argue that the ruling non-Taliban Afghan regime was not even allowed to fight out the Taliban lest it would lead to unprecedented bloodshed; but they would aver that such fight could have led to a stalemate and a mixed government and the spectacular advancement on the front of women rights could have been salvaged.

At this juncture, since individual countries seem to prefer their short-term interests, the UN with its global mandate should lead the campaign for ensuring women and minority rights in Afghanistan. This can be done in three ways: one, despite its flaws, the UN remains the only international body that has some legitimacy and can act as an arbitrator to broker an agreement, even with the Taliban by offering them something in return, like aid that the Taliban need gravely but conditioning it with engagement of women agencies, like NGOs/ run by them.

The UN can employ some Afghan women in its teams that deal with the Taliban, conveying the message that allowing women to be part of the polity may benefit the Taliban regime on the economic, social and political fronts. Such possibilities do exist as it seems that some sections of the Taliban are not averse to the idea of women rights and education. Those sections can be empowered by making them to deal with the UN and its teams. For that, an environment needs to be created for having freewheeling discussions about how the policy can help the country over time.

The UN can mobilise various countries that engage the Taliban out of their fear that Afghanistan may again become a nursery of terror and ask them to subject their investments in Afghanistan to Taliban guaranteeing the rights of all sections of the Afghan society. This will bring long term stability to Afghanistan which can also help in preventing the use of the Afghan territory by terrorists. The international community can also use the UN to make humanitarian aid available to the people of Afghanistan in a manner that would make the Taliban dependent on the UN and its requirements and hence amenable to its persuasions to modify their behaviour in an incremental manner. Thus, engagement with the Taliban needs to continue but its nature and scope should be redefined to ensure that the people of Afghanistan enjoy their rights without being encumbered by values that the Taliban seek to promote through a regressive interpretation of their religion and culture.

*Dr Nazir Ahmad Mir & Dr Muneeb Yousuf are working as research analysts in projects in Manohar Parrikar Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses (MP-IDSA). The views expressed here are their own.

Endnotes

2. Rahim Faez, “UN-led meeting in Qatar with Afghan Taliban is not a recognition of their government, official says”, Associated Press news, 2 July 2024

3. “UN envoy defends failure to include Afghan women in upcoming meeting with the Taliban in Qatar | AP News”, AP News, 22 June 2024.

4. “Doha Meeting on Afghanistan Provides Critical Opportunity to Discuss Women’s Rights, Speaker Tells Security Council”, UN Meetings Coverage and Press Releases, 21 June 2024

5. Ayaz Gul, “Taliban stand firm against negotiating women’s rights at Doha”, VOA, 29 June 2024.

6. Bais Hayat, “Taliban leader suggests implementing Sharia law could lead to stoning, beating of women”, AMU, 24 March 2024.

7. Dina Elbasnaly and Lewis Sanders IV, “Women's rights in Islam: Fighting for equality”, DW, 5 May 2022.

8. Cited in D. Lyn Hunter, “Gender Apartheid Under Afghanistan’s Taliban”, 17 March 1999

9. Ibid.

10. “Taliban replaces ministry for women with ‘guidance’ ministry”, Aljazeera, 18 September 2021.

11. Ayaz Gul, “UN: Afghan Taliban increase support for anti-Pakistan TTP terrorists”, VoC, 11 July 2024. For the original report see https://www.undocs.org/S/2024/499

Comments