* This Essay was published in Strategic Analysis, July-August 204, (Vol. 48, Issue 4, pp. 375-395), at https://doi.org/10.1080/09700161.2024.2406184. This is being reproduced here with due permission.

India and Pakistan fought their first war over Kashmir soon after independence and it ended with a ceasefire coming into effect on 1 January 1949. Thereafter, talks commenced to delimit, demarcate and delineate a ceasefire line (CFL) between the two sides. On 27 July 1949, under the auspices of the United Nations Commission for India and Pakistan (UNCIP) the Karachi Ceasefire Agreement (CFA) 1 was signed. Even though this agreement delimited the CFL till the glaciers, yet it was subsequently demarcated only till grid reference NJ 9842, a point lying well short. Maps delineating this line were duly signed and exchanged by both sides and the United Nations Military Observers Group for India and Pakistan (UNMOGIP) was constituted to ensure peace and tranquility around it. As envisaged in the CFA, both India and Pakistan maintained status quo beyond NJ 9842 since the region was pending mutual demarcation and delineation by the local commanders under the supervision of the UN Observers. Since this region never had any military presence, it remained demilitarized and did not see any action either in 1965 or 1971. The Line of Control which emerged in 1972 after the Simla Agreement, also terminated at NJ 9842, with neither side pressing for any demarcation beyond it.

The terms of the CFA were obviously very clear to both the countries as neither raised any doubts about it after execution nor sought to disturb the mutually agreed status of the region beyond NJ 9842 – something they could have easily done at any time, in war or peace. Despite the CFA stipulating that the CFL would run north to the glaciers and this position would remain unchanged after 1972, Pakistan unilaterally drew an imaginary line joining NJ 9842 with the Karakoram Pass and not only staked claim to the entire region to its west through its protest notes of 1983 but also started planning to physically occupy it.2 This triggered a chain reaction which culminated in India moving its troops to the Saltoro Heights on 13 April 1984 to pre-empt Pakistan from altering the status quo to its advantage.3 It was only to counter the Indian presence that Pakistan started building a case in hindsight to defend its newly-discovered claim line from NJ 9842 to the Karakoram Pass.4 But how did this line first appear? How did it disappear? What are the common misconceptions about it? Does it have any legal basis? Why does it continue to exist in some maps even today? These are some important questions which merit consideration to appreciate the facts surrounding the Siachen impasse in their correct perspective.

The Beginning: Extension of the CFL between 1949 and 1968 in private publications

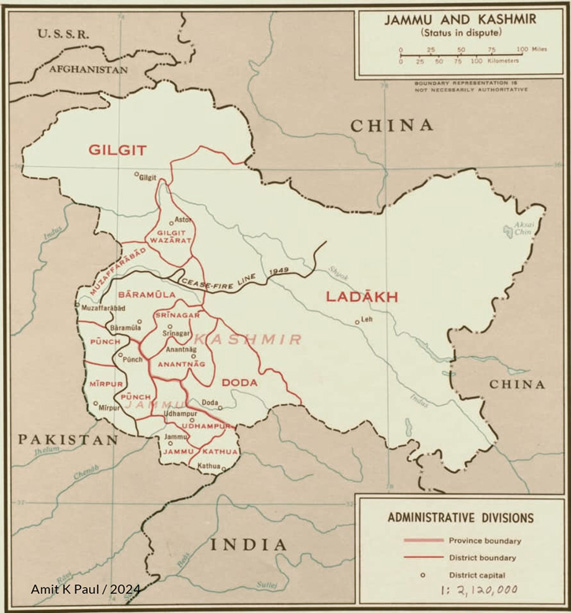

After the execution of the CFA in 1949 several books, papers and articles were written on Kashmir. For all those interested in depicting the State in maps it was incumbent that, as a rule, they reproduce the CFL without deviating from the delineation agreed in the UN maps5 (Refer Figure 1).

Unfortunately, this did not happen and distortions crept into the discourse from the 1950s itself. While a majority of the authors left the CFL hanging in the air pointing due north as per the CFA,6 some others chose to twist its alignment towards the end and/or extend it to meet the State boundary at such a point where they deemed appropriate.

A map suggesting a vertical extension of the CFL due north as per the CFA, appeared in the New York Times on 5 July 1953, when Robert Trumbull in his article, ‘India and Pakistan near pact to split Kashmir, avoid vote’ reported on a possible division of Kashmir with the region lying west of a line drawn northwards from NJ 9842 till the State boundary, likely to be given to Pakistan. This map was subsequently reproduced by Ghulam Mohammad Mir Rajpori and Manohar Nath Kaul in their 1954 work Conspiracy in Kashmir (Social & Political Study Group, Amirakadal, Srinagar). However, one of the earliest works in which the CFL was extended with a curved line meeting the State boundary, is Horned Moon: An Account of a Journey through Pakistan, Kashmir and Afghanistan, by Ian Stephens (Chatto and Windus, London, August 1953). Interestingly, in Stephen’s map even though the CFL visually appears to have been extended north as per the CFA, yet it actually meets the boundary near the Karakoram Pass since the orientation of the State itself in the map is incorrect. Thereafter, Prem Nath Bazaz (The History of Struggle for Freedom in Kashmir, Kashmir Publishing Co, New Delhi, 1954) and Rushbrook Williams7 (The State of Pakistan, Faber and Faber, London, 1962) followed suit and Bazaz’s map was subsequently reproduced by P.L. Lakhanpal in 1958 (Essential Documents and Notes on Kashmir Dispute, International Publications, New Delhi). It is pertinent to note that during this period none of the official maps issued by Pakistan extended the CFL beyond NJ 9842, though some of them liberally distorted its orientation towards the end.8

While some atlases of the 1950s depicted Jammu and Kashmir distinct from both India and Pakistan and steered clear of showing the CFL, others ventured into troubled waters. With multiple versions of the Line floating around in various publications, it was not long before they too fell in error. In the 1956 Penguin Atlas of the World, the CFL is shown as a broken line of separation extending from NJ 9842 to the Karakoram Pass. However, John Bartholomew’s Times Atlas of the World (1959), and his 1:400000 map of India, Pakistan and Ceylon published the following year, join NJ 9842 with the Karakoram Pass with a curved line. In stark contrast, the Times Atlas of the World, Comprehensive Edition (1977), shows the CFL running west of the Siachen Glacier and joining with the China border at a point which is about 60 miles west of the terminal point shown in the 1980 edition.9 Interestingly, the 1980 terminus itself is not the Karakoram Pass but a point lying much to its west cutting across the Rimo glacier. Similarly, the Times Atlas of World History (1979), in its chapter on Southern Asia shows the CFL meeting the State boundary at a point west of Siachen near Sia Kangri.

The Times Enquiry

In view of the aforementioned inconsistencies, and the Line hovering between two extremes in different editions of the same atlas, Professor Joseph E Schwartzberg wrote to Ms. Margaret Wilkes, Map Librarian at the National Library of Scotland on 22 August 199410:

‘I am writing to you at the suggestion of Valerie Scott, a fellow member of IMCOS in respect to a matter of considerable political sensitivity. It involves the manner of depiction on many maps of South Asia of the cease-fire line in Kashmir agreed to by India and Pakistan, effective 1 January. 1949. The agreed south west terminus of this line lay on the border of Kashmir with West Punjab while its northeastern limit was UTM grid point NJ 9842. Many maps, however, including some issued (for a time, but no longer) by the US Defense Mapping Agency have shown an extension of the cease fire line by a more or less straight diagonal drawn northeastward to Karakoram Pass on the de facto Sino Indian border. There is, to the best of my knowledge no legal basis for such a depiction; and the US Defense mapping Agency has come in for repeated criticism by authorities in India, some of whom have incorrectly suggested that it is based on an anti-Indian position in respect of the Kashmir dispute on the part of the US Government. More seriously since April 1984 there have been numerous armed clashes between India and Pakistan in the Siachen Glacier area to the north of point NJ 9842 because of Indian attempts to block what it perceived to be the extension of Pakistani control eastward to Karakoram Pass.’

‘I have tried to ascertain the root cause of the frequent erroneous depiction referred to in the preceding paragraph. The earliest map that I have seen that shows the extension to the Karakoram Pass is Sheet No 31 of Volume 2 of The Times Atlas of the World, Mid-Century Edition dated 1959, for which the mapping firm of Bartholomew and Sons was responsible. The following year, Bartholomew’s 1:4,000,000 map [of] India, Pakistan, [and] Ceylon showed a similar depiction. I suspect but cannot prove that these two maps from internationally respected and generally authoritative sources formed the basis of similar subsequent depictions of the ceasefire line by many mapping agencies. The questions that now concern me are these: On what basis did Bartholomew extend the cease fire line to Karakoram Pass? Was there any earlier map or legal document that they followed in doing so? Or was the extension, as I suspect simply an ill-advised cartographic decision based on a sensed need for closure in the depiction of what had by 1959 become a de-facto boundary?’

On 30 March 1995, Harper Collins Cartographic responded to these queries through their Data Administrator, R E Pountain after looking into the matter and speaking to John Bartholomew:11

‘The approximate history of our mapping of this Section in the Times Comprehensive Atlas is as follows. For the Mid-Century Edition in the 1950s we showed a straight line joining the line of Control with the Karakoram Pass. This was long before my time with the company (I joined in 1974) but John is certain that it was done based on an original map source, of which we now regrettably have neither any record nor memory. He also says that we later saw official wording, presumably derived from an Indo-Pak agreement that supported the straight line to the pass interpretation, although we do know that, that must have been an informal description rather than an actual delimitation of the boundary. Later on, many news reports of course described the periodic upsurges in fighting on and around the Siachen Glacier, well to the west of the Karakoram Pass. Based on these reports, John plotted an interpretation which was likely to be very much closer to the truth. The military situation there would no doubt have been somewhat fluid; and neither side would be prepared to divulge exactly where their forces were at any one stage. The boundary that was shown on the Times Comprehensive during the 1970’s was therefore the best interpretation which we could derive and we believe it still is, since it is clear that both sides have stayed pretty much where they have been for years despite the huge input of resources. Complicating the issue slightly, the editors of the Times Atlas in 1980 decided to revise this unsettled part of the boundary back to a straight line interpretation. Now unfortunately we cannot trace the reasons for this, because those chiefly involved at that time, whether at (what used to be) Bartholomew in Edinburgh or Times Books in London, are no longer with us. In fact it seems to have been done as a last minute decision because the correction does not feature in the editorial correction instructions at the time –our librarian Ken Winch has ascertained this. It is quite an unusual situation in that respect. What appears to us to be clear now is that we should revert to our 1970’s interpretation.’……………

‘I am just sorry that none of us can shed any more detailed light on the information sources. We do not keep detailed records of reasons for decisions, because it would be too laborious and too rarely needed. Nevertheless, what we believe is certain is that the ‘straight line to the pass’ was not our invention! We feel it is unlikely that the largest mapping agencies whether government or commercial would simply have copied from the Times Atlases or other Bartholomew mapping without using their own primary sources, at least on such a serious political issue. I should say it is more likely that they also had access to the same sources as ourselves at roughly the same time’ (Emphases added).

Bartholomew and Pountain are incorrect in reiterating that the 1959 extension of the Line was based on an original map source or some official wording in an Indo-Pak understanding as the only primary source documents in existence at that time were the CFA and the UN Maps accompanying it. The CFA did not mention anything about the Line going to the Karakoram Pass and the UN Maps clearly show it terminating well before the State Boundary. Even assuming that someone plotted a line based on an interpretation of that document then also it should have proceeded north from the last mutually demarcated point as envisaged and not eastwards towards the Karakoram Pass as shown by the Times. Further, at this time such an extension was also not visible in any of the maps produced by the US Government, India or Pakistan. Therefore, the possibility of anyone having access to any official sources which exhibited or implied such a position is out of the question. It is also not clear as to which reports Pountain is referring to regarding skirmishes around Siachen in the early 1970s as there were none because, admittedly, neither side had any military presence in the region. In any event, even assuming there were some, it ought not to have had any bearing on the depiction of a line in a map. The self-exculpatory nature of the response shows that other than assumptions and interpretations, there was no concrete legal or factual reason for the depiction of the line by the Times. The admitted variation in its depiction the 1950s,1970s and 1980s with John Bartholomew plotting it according to his interpretation, shows that even during this period, Times could hardly have been considered an authoritative and credible source on this issue. Nevertheless, being a popular atlas, the possibility of other publications (for example-The Reader’s Digest Great World Atlas 1963) following it or treading on the same path and falling into the same error, cannot be ruled out (Emphases added).

Maps by the US Government

Between 1950 and 1968 several maps, background notes and publications showing Jammu and Kashmir were produced by various US Government agencies. These included charts for military and navigation purposes as well as maps produced by the CIA and the State Department. All these publications depicted the status of the State as ‘disputed’, but importantly whenever they did show the CFL, it was never extended to the State boundary. However in 1964, an artist Bill Perkins made a Kashmir Headline Focus Wall Map titled ‘Kashmir: Where three powers compete’, for a private company Civic Education Services Inc., Washington DC. This map was meant for circulation in schools and joins the CFL and the Karakoram Pass with a curved line similar to the one in Times 1959. In contrast, the Tactical Pilotage Chart, TPC G7D titled China, India, Pakistan, compiled in November 1967 by the US Army Map Service, joins the CFL to an Air Defence Information Zone (ADIZ) line going straight from NJ 9842 to the Karakoram Pass12. However, since ADIZ lines only provide zoning boundaries for Air Traffic Controllers and have no connection with the boundaries of a State, therefore, even though TPC G7D creates a visual impression of their being a straight line of separation between NJ 9842 and the Karakoram Pass, subsequent maps produced

by the State Department, did not follow it13 (Refer Figure 2: Map of 1968).

A scrutiny of the maps produced by the US Government till September 1968 shows that barring the visual aberration created by the ADIZ map of 1967, the American policy was to depict the CFL terminating well before the State boundary in accordance with the CFA. Details of when and how a tectonic shift took place in this policy became public only after the State Department declassified some documents around 2014 and Freddie Wilkinson broke the story in 2021.14

September 1968: Appearance of Hodgson’s Line

Between 1966 and 1968 there is ample record to show that efforts were being made by Indian diplomats to ensure that the US remove the ‘in dispute’ status of J & K from its maps and depict its boundaries correctly. Two Airgrams on this subject, A-415 dated 2 December 1966 by Chester Bowles, and A-1245 dated 27 June 1968 by William Weathersby, were sent by the US Embassy in New Delhi to the State Department apprising them of Indian concerns and seeking guidance on how to represent India’s borders in American maps.

The task of resolving this issue fell on Robert D. Hodgson, an Assistant Geographer with the Office of the Geographer, State Department, US Government. On 18 September 1968, Hodgson issued a fresh directive to the Chief of Mapping and Charting, Defense Intelligence Agency as well as the CIA and responded to the queries of the US Embassy in India vide Airgram A-418.While dealing with the depiction of the boundary of Jammu and Kashmir and the CFL, he directed that henceforth the 1948 cease-fire line in Kashmir will become the limit of administration between India and Pakistan. The boundary will be shown in a line style distinctive from that normally used for an accepted international boundary. The line in the legend may a) be identified as an ‘other line of separation or sovereignty’ b) be called the 1948 cease fire line or c) remain unidentified. The choice will be determined by the purpose and the scale of the map. Finally the ceasefire line should be extended to the Karakorum Pass so that both the States are “closed off”. Jammu-Kashmir State may be identified on the map as required or as space permits, but the “status in dispute” note will be deleted. The general disclaimer, however will be retained.15

To assist the Embassy it was also proposed that a map will be made in Washington which would incorporate these changes and copies would then be made available for use. It was also decided that a restricted order will be issued to the Federal mapping offices to change their representations of Indian international boundaries on official maps as and when they are revised so that less public attention is called to the change even though it would have meant that for a certain period official maps would be available with contradictory boundary alignments and sovereignty treatments. David Linthicum, a retired cartographer from the Office of the Geographer and Global Issues at the US State Department suspects that a mapmaker’s fastidious desire to resolve ambiguity might have played a role in Hodgson closing off the boundaries rather than leave the line hanging in the air. ‘Some people have the completeness syndrome or completeness obsession where you have to fill in the gaps.’ If both countries were to be ‘closed-off’ as Hodgson wrote, the line would need to reach China to form a complete boundary- and the Karakoram Pass was the most identifiable point on the divide.16

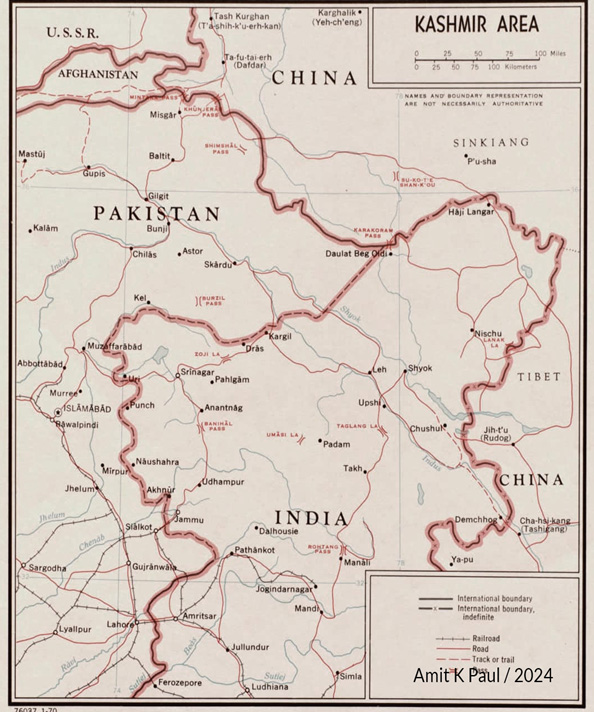

After Hodgson’s directive there was a visible change in the American Policy of depicting the CFL in its maps. While earlier (i.e., from 1949 to 1968) the CFL ended well short of the State boundary, now it was being extended to the Karakoram Pass17 (Refer Map 3)

in a straight line and in some maps (contrary to even Hodgson’s guidance) even being shown akin to a formal international boundary of Pakistan.18 Thus a completely new line came into existence which depicted the entire region to its west as part of Pakistan. Since this line was neither an international border nor the actual CFL agreed between India and Pakistan, nor the line delineated in the UN maps, Freddie Wilkinson refers to it as Hodgson’s Line.

Being one of the largest and most influential map maker in the world, commercial map makers were bound to be influenced by whatever was being published under the seal of the US Government and therefore after 1968, in the midst of various publications showing the correct position of the CFL, Hodgson’s line too started becoming visible.

Inconsistencies in American maps even after Hodgson’s guidance

While in the 6th edition of the Operational Navigation Chart ONC G-719(1980), titled Afghanistan, China, India, Pakistan, USSR, originally compiled in 1974 by the Defense Mapping Agency (DMA) Aerospace Center, Missouri, the CFL is depicted like an international boundary (contrary to Hodgson’s guidelines) and extends to the Karakoram Pass, in the inter chart relationship map on the same sheet, it is shown distinct from it. However, in DMA’s 1983 Combined Joint Operations Graphic (JOG) Series 1501C, edition 1, Sheet NI 43-4 titled Chulung, Pakistan, China, India,20and the location diagrams accompanying its JOG Series 1501 (Air): 1981, edition 3, Sheet NI 43-2 titled Gilgit, Pakistan ; 1981, edition 1, Sheet NI 43-7, titled Kargil, Jammu and Kashmir and 1986, edition 2, Sheet NI 43-3 titled Skardu, Pakistan, China, the position is entirely different.21 In all these maps the line terminates well before the State boundary without being extended to the Karakoram Pass.

This depiction of the Line without any extension in 1981, 1983 and 1986, contrary to Hodgson’s guidance of 1968 but with the extension akin to an international boundary in 1974/1980, shows that even within various mapmaking agencies of the US Government there was considerable confusion still persisting on this subject.

March 1987: Disappearance of Hodgson’s Line

On 3 December 1985, Dr. S. Jaishankar, then First Secretary, Embassy of India, Washington DC raised the issue of depiction of J&K in the American Maps and wrote to the Pentagon pointing out that, maps of South Asia in the Defense Secretary’s Annual Report and Military Posture Statement for FY 1986 fail to correctly depict India’s international boundaries and were not in accordance even with the US policy on the subject as conveyed by the US Embassy in New Delhi in the past.22 On 27 February 1986 George Demko, State Department Geographer acknowledged that ‘DoD’s cartographic depiction of the India-Pakistan boundary which shows all of Kashmir in Pakistan in the Secretary of Defense’s Annual Report to Congress for FY 86, is not in conformity with long established US policy’.23 Thereafter on 12 March 1987, Demko issued fresh guidelines to eliminate future incorrect portrayal of the boundary on all Federal products stating that in an effort to update the mapping guidance and eliminate future incorrect portrayal of this boundary on Federal products the following instructions are issued for immediate implementation. The cease fire line between India and Pakistan must be shown on all cartographic products. The cease fire line which extends approximately to 35 N, 77 E is categorized as ‘other line of separation’ symbolized on the map by a dashed line (--). On maps of a scale of 1:50,000,000 or larger the cease fire line will not be extended to the Karakorum Pass as has been the previous cartographic practice. The cease fire line should be labeled where map scale permits. The guidance also specified that if colour is used then the land tones should be shown using alternate colour bands indicative of the colour representation of both India and Pakistan.24

Thus, on 12 March 1987 the US Government effectively admitted that the depiction of the CFL in its products was incorrect and the cartographic anomaly was rectified by issuing a new guidance. Hodgson’s Line, which had been erroneously introduced in 1968 and had been subsequently followed by many, stood erased.

US map-making agencies admit their mistakes

After Demko’s directive, new State Department maps started emerging in which the Line terminated at NJ 9842 instead of being extended to the Karakoram Pass. However, despite the clear directives, some American maps continued to show the Siachen region in the same colour tone as Pakistan.25

In view of these inconsistencies, on 28 December 1991 Prof. Robert G. Wirsing wrote to the US Government enquiring about the depiction of an international boundary between the end of the India/Pakistan ceasefire line and the Chinese border by the Defense Mapping Agency in ONC G-7(supra). On 3 January 1992, Joel M. Litman, Colonel USAF and Assistant Deputy Director for Programs, Productions and Operations, DMAAC, responded admitting that in ONC G-7 edition 7, a boundary had erroneously been shown linking the ceasefire line with the China border and confirmed that, ‘DMAAC realized in 1988 that our product was incorrect and indicated to our users with the Chart Updating Manual (CHUM) that this boundary was portrayed incorrectly. During the next production cycle of this chart we will correct the boundary appropriately.’ 26 Thereafter, Dr. William Wood, Geographer, State Department confirmed on 31 January 1992 that the representation on ONC G-7 is erroneous. It has never been US policy to show a boundary of any type closing the gap between NJ 9842 and the China border. I enclose a copy of the guidance issued from this office on March 12, 1987, specifically stipulating no boundary line in that area. This guidance does make reference to the previous practice of closing the gap, which may be partially the origin of the error on ONC G-7. The defense mapping Agency is in possession of our guidance but ONC G-7 was compiled in 1974, 13 years before the guidance was issued. Except for the aeronautical information this chart has not been revised. When the base data for it are revised, we will ensure that the international boundary symbol is removed from the gap area. A correct representation of the situation is given on the 1:500,000-scale Tactical Pilotage Chart of the area (TPC G-7D).This chart was revised in 1986. The ADIZ line on this chart still connects the end of the ceasefire line with Karakorum Pass, but there is no black boundary line symbol underneath it. A purple line appears that is the edge symbol for an ADIZ. The gap in the ceasefire line has created certain difficulties with production of maps with tinted national territories and with digital cartographic databases. The attached guidance addresses the color map problem on page 2 with a traditional technique that may give the most realistic depiction. In practice cartographers usually draw a “tone cut line” from NJ 9842 to the Karakorum Pass—an edge to whatever tones are used for Pakistan and/or India without any line symbol. For relational digital databases however, the use of the inter-fingered bars in our guidance is cumbersome. A national territory has to have a closed polygon in these databases. The simplest way to accomplish this in this area is to close the gap with a straight line from NJ 9842 to the Karakoram Pass. The cartographers are instructed, however to identify that segment as having “no defined boundary”. The drawing of tone cut lines or polygon boundaries where no boundaries exist is not unique to the Kashmir area. The same practice is used in the Arabian Peninsula where boundaries are not defined. It does not in any way indicate a US Government policy that there is a boundary line in such places. The choice of Karakoram Pass as the northern terminus of the tone cut or polygon closing line from NJ 9842, undoubtedly (emphasis added) has its origin in the China/Pakistan agreement of 1963, which implicitly defined the territory “under the actual control of Pakistan” as extending eastward to that pass. Even so, these lines do not signify a US Government position on the limits of Pakistani or Indian territory.27

Around 1994, B.G. Verghese too raised this issue with Prof Schwartzberg28 who took it up with the concerned authorities in the US and elsewhere. On 26 April 1995, Dr. William Wood, Director, Office of the Geographer and Global Issues while responding to Prof. Schwartzberg’s query on why the ceasefire line had been extended in the past, confirmed that. ‘We do not know what has given rise to the custom on US maps showing the straight line connection from NJ 9842 to the Karakoram Pass. On maps with political coloring, however, we connect NJ 9842 to Karakorum Pass with the same tone cut line and in digital databases we would use the same line, identified as ‘no defined boundary’. This may be related to the recognition by the US (IBS No 85) of the China/Pakistan boundary agreement of 1963, which extends eastward to Karakoram Pass, but the evidence from Harper Collins suggests that the practice began earlier than this agreement’.29

Thus while the US map making agencies acknowledged their mistakes they attributed the error to everything else but Hodgson’s directive as records pertaining to it were classified. If the appearance of Hodgson’s Line at some point of time in history sowed the seeds of a possible claim in Pakistan, it is only logical to assume that its disappearance should have had the converse effect. Unfortunately for the subcontinent, this did not happen as Pakistan continued to justify its presence by giving specious arguments. One such theory propounded after 13 April 1984 connected the appearance of this line to the Sino-Pak border agreement of 1963.

The myth of CFL’s extension being connected to the Sino-Pak Agreement of 1963

The 1963 China-Pakistan agreement did not recognize Pakistan’s sovereignty over the region and hence its competence to enter into any agreement vis-à-vis the boundary of the State of Jammu and Kashmir. In admitting the possibility that the ‘sovereign authority’ empowered to reach a final settlement– hence in possession of the territory south of the border with China– might be India, the agreement left the door open in respect of permanent sovereignty over the area in which the Siachen Glacier is found. The agreement’s preamble described the territory lying south of the agreed boundary as the “contiguous areas the defense of which is under the actual control of Pakistan” and not as Pakistani territory.30 This Agreement was rejected by India which not only lodged a protest but also came out with a White Paper, giving the factual position accompanied with maps, in which the CFL was clearly terminated at NJ 9842. The Indian position was also communicated to the President of the UN Security Council vide a letter dated 16 March 1963.

Perhaps the first popular linkage of Hodgson’s Line with the 1963 Sino-Pak Agreement was made by Prof. Robert G. Wirsing when he was a visiting Fullbright Scholar in Pakistan in 1986. It is only thereafter that this proposition appears to have been adopted by various commentators in their bid to create some semblance of a Pakistani claim to this region. While conceiving Pakistan’s possible case for Siachen, Prof. Wirsing contended that the logic of Pakistan’s position in this regard is reinforced by the fact that the Karakorum Pass was also the terminal point of the boundary delimitation agreed between Pakistan and China in 1963.31 However, while asserting so, he completely ignored the fact that it was highly illogical and legally untenable for Pakistan to first execute a delimitation agreement till a point which was neither in its possession nor under its control and then subsequently claim territory till that point on the basis of that very agreement.

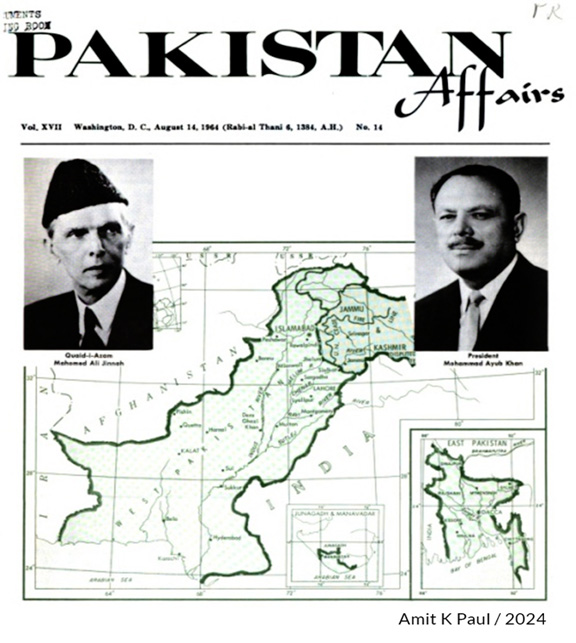

In fact, this is the reason why, even after the 1963 agreement, the entire region to the east of Indira Koli continued to remain un-demarcated. The Karakoram Pass was and continues to be an agreed boundary point only between India and China and if Pakistan had exercised any control on the defense of the contiguous areas as falsely claimed, then the question of India moving onto the Saltoro Heights in 1984 from those very areas would not have arisen. It is pertinent to note that even though the 1963 agreement describes in words the boundary line between China and Pakistan along the mountain peaks contiguous to Sinkiang till the Karakoram Pass, it does not make any reference to NJ 9842 or the region between NJ 9842 and the Karakoram Pass. Further, no official map of Pakistan after the 1963 agreement, including the official 1:500,000 ‘Map of the boundary between China’s Sinkiang and the contiguous areas, the defence of which is under the actual control of Pakistan’, released by the Survey of Pakistan in 1966,32 shows the extension of the CFL to the Karakoram Pass, something which Pakistan claims (post-1984), is implicit in that agreement. On the contrary, in all official maps of Pakistan showing the CFL (for example, the map published by its Embassy in the US in 1964 in a special issue of Pakistan Affairs33 on the 17th anniversary of Independence) it terminates at NJ 9842 without being extended to the Karakoram Pass (Refer Figure 4).

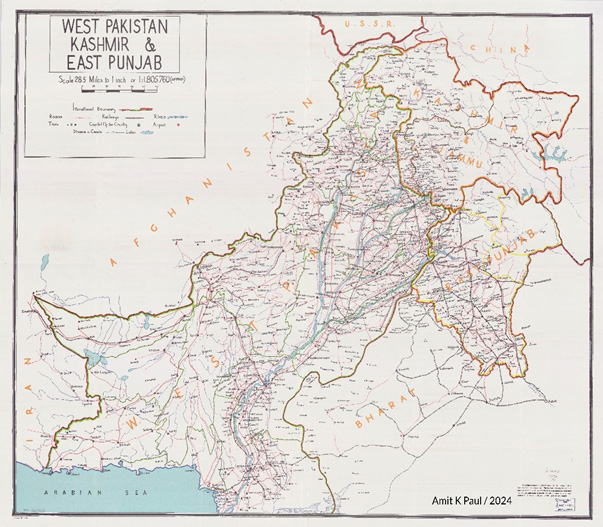

Interestingly, Ferozsons, one of the oldest and most well reputed book publisher/store in Lahore published a map book in 1966/67 and then again in 1971, titled ‘Map of West Pakistan, Kashmir,

East Punjab and Rajisthan showing International Boundaries and Cease-Fire Lines of 1947 and 196534 (Refer Map 5).

In this the CFL has been extended northwards as per the CFA in a smooth curve and joins the Jammu and Kashmir State boundary at a point which is due north of NJ 9842 near Sia Kangri. The map clearly mentions that the boundary between Pakistan and India and the October 65 cease fire line have been entered in accordance with the best information at present available in conjunction with proper authorities. However its alignment on this map is not authoritative. This is of significance because it explicitly deals with the CFL and has been published with the imprimatur of the military authorities who would have been prompt to act if it had depicted anything which was contrary to the official or popular understanding. Thus, it is apparent that during this period, officially and even unofficially, the idea of extending the CFL till the Karakoram Pass leave alone staking claim to the region beyond NJ 9842, had not even taken birth in Pakistan. Further, the extension of the CFL due north as per the CFA in both maps produced years apart shows that there was never any confusion even within Pakistan as to where the Line would go if at all it were to be extended beyond NJ 9842.

For the sake of argument, even if it is assumed that at some point Pakistan did believe in the legally untenable proposition that its bilateral agreement with China implied an automatic amendment of its bilateral agreement with India, and hence an implied extension of the CFL till the Karakoram Pass, then apart from showing such an extension in its own maps, it ought to have taken up the matter with India or seriously pursued it. However, there is no contemporaneous record of this issue having been raised by Pakistan in any of its engagements in any forum including the UN. Notably, there is also no reference to any such implied extension or claim line or dispute in the region beyond NJ 9842 by Mujtaba Razvi in his seminal work, Frontiers of Pakistan (National Publishing House Ltd, Karachi-Dacca, 1971) in which he has dealt extensively with all issues concerning its boundaries.35 Conversely, there is ample cartographic evidence to show that during this period Pakistan, being well aware that any attempt to change status quo on the ground or in maps would be a violation of the CFA which could possibly jeopardize its Kashmir case in the UN, refrained from showing the entire state of Jammu and Kashmir as part of its own territory, even after its 1963 agreement.36 Therefore the assertion that it conjured the existence of a line within the state and hypothetically appropriated for itself control over a part of its territory as a consequence of that agreement, is clearly without merit. This conclusion is fortified by Pakistan’s admitted position after 1984 that it had been complying with the CFA since 194937. That being so, the question of any perceived extension of the CFL taking place in 1963 in derogation of the CFA does not arise.

Clearly Riaz Mohammad Khan’s assertion that Pakistan assumed the existence of an imaginary line joining NJ 9842 with the Karakoram Pass to be the extended LoC post its provisional agreement with China38 is an afterthought. However Khan is correct when he fairly admits that the Sino-Pak agreement is provisional and the CFL’s extension is unilateral, assumed and imaginary, thereby impliedly conceding that it is of no use legally or otherwise.

Hodgson’s Line: An innocuous error or a Western conspiracy?

Prima facie, the argument that the American policy change of 1968 cartographically gifted this region to Pakistan due to some sinister machinations appears attractive especially because Pakistan had a mutual defence assistance agreement with the US in 1954 and joined SEATO and CENTO the subsequent year. However, this may not be entirely correct. If the 1959 US-Pakistan bilateral pact was severely criticized in China, the Americans were equally displeased with the China-Pakistan agreements of 1963 and also protested against Chou En-Lai’s visit to Pakistan in 1964. The US’s displeasure with China due to its nuclear explosion and the CIA’s attempts to spy on their programme, are also well recorded. If the US really wanted to gift Siachen to Pakistan in lieu of its services or otherwise, then it would have revised its maps in 1963 itself when the Sino-Pak agreement was signed. However, this did not happen. On the contrary, after 1963, it produced several maps, which did not extend the Line to the Karakoram Pass. It is obvious that the Americans, like everyone else knew that Pakistan’s provisional agreement with China which defined its border till a point which was not even in its physical possession, was legally untenable, and with India not being a party to it, there was no question of it affecting the CFL. A perusal of the State Department records between 1964 and 196839 shows that during this period the US Government played an active role in prodding India and Pakistan towards a mediated settlement on Kashmir, with several proposals being discussed over time. However, in all these documents there is a conspicuous silence on Pakistan’s perceived extension of the CFL to the Karakoram Pass with this issue neither being raised by it nor being the subject matter of any discussion. Therefore, it appears unlikely that the US, which was busy with the war in Vietnam in the late 1960s, would have changed its policy on the depiction of a line in a map between India and Pakistan in a region where there was no dispute or disagreement between them.

Further Wood’s ‘undoubtedly’ in 1992 to Wirsing turning into a ‘may be ’in 1995 to Schwartzberg appears to be a tacit admission of the fact that the extension of the CFL from NJ 9842 till the Karakoram Pass by his office had more to do with the over enthusiasm of one of his predecessors to close the boundaries to overcome the difficulty in map-making rather than any other strategic reason. It is pertinent to note that the International Boundary Study on the China-Pakistan Boundary issued by the State Department (IBS No. 85) which Wood is referring to is dated 15 November 1968. This is almost two months after Hodgson issued his guidelines in September 1968. Thus, the dotted line originating from the Karakoram Pass in the China-Pak boundary map attached with IBS 85 (albeit with the disclaimer that the depiction of boundaries therein is not authoritative), could only have been a consequence of Hodgson’s directive and not the other way round. Hodgson’s choice of Karakoram Pass as the natural closure point appears to stem from the fact that this was an agreed boundary point between India and China. With India physically present both at NJ 9842 and the Karakoram Pass, Hodgson probably assumed it to be the most recognizable point on the State boundary where the Line could be extended rather than any other random point.

From the material thus far it emerges that the sudden appearance of Hodgson’s Line may be largely due to cartographic convenience and the desire to close off the boundary instead of leaving it hanging in the air. However, whether the same can be said about its continued presence till 1987 is open to debate.

The effect of the CFL’s extension to the Karakoram Pass

Post-1949, Pakistan’s Kashmir policy focused on highlighting the entire state as a disputed territory pending plebiscite. Therefore, the thrust of the Indian diplomatic effort also appears to have been to get the phrase ‘Status in Dispute’ removed from all American maps, consistent with India’s policy that the entire state was legally an integral part of India. It appears that both the countries were more concerned about the disposition of the entire state and therefore did not pay much attention to this cartographic change, which was gradually introduced by the Americans. Apart from the bilateral agreements this could be another reason why despite this cartographic anomaly Pakistan never replicated it in any of its official maps or staked claim to the region beyond NJ 9842 on that basis. The fact that there was no dispute beyond NJ 9842 even after the 1971 war is evident from the Suchetgarh Agreement which too terminated the LoC at NJ 9842. It appears that at least till this time both sides were happy with the status quo in the region in terms of the ground position (area being unoccupied and demilitarized) as well as the paper position enunciated in the CFA (area pending demarcation and delineation).There is no documentary evidence to show that either side attached any significance to Hodgson’s Line (if at all they were aware of it), because despite its presence neither side appears to have taken note of it nor raised any claim or counter-claim to this region based on it, when the demarcation/delineation of the LoC was being done.

The Karakoram Range is a paradise for mountaineers and its most popular peaks like K2, Broad Peak etc. are easier to access from Pakistan. A natural and obvious consequence of prominent atlases showing the entire region west of Hodgson’s Line in Pakistan was that many expeditions which sought permission from Pakistan to explore the Karakorams, also started seeking permission to cross the Saltoro Ridge to explore peaks to its east. Instead of denying permission to these expeditions and maintaining status quo, Pakistan readily obliged and started sending its military liaison officers with the teams. Obviously, neither side was policing each and every inch of this hostile terrain, therefore details of expeditions crossing the Saltoro from the Pakistani side emerged only when they were written about in various mountaineering journals and dug out by the Indians in 1978, when their interest in the region was triggered after Col. Kumar’s chance meeting with two German explorers.40 In contrast, India did not permit any international explorations in the region and maintained status quo therein as envisaged in the CFA. However, in 1958, the Geological Survey of India conducted a three-month long snout survey of the Siachen Glacier as part of its commitment to commemorate the International Geophysical Year.41 Even though this was an official survey sanctioned by the Government of India and was well publicized in international academic circles, there was no protest from Pakistan on the Indian presence on the glacier for over three months. It appears that since explorations and scientific visits did not pose any threat, or give either side any reason to apprehend that the other may physically occupy the region contrary to the mutual understanding, not much importance was given to them by both the countries. In fact, one of the first mainstream article on the possibility of mountaineering activities’ being used to alter established territorial boundaries was written by an Indian journalist Joydeep Sircar, when he gave details of all explorations taking place in this region in High Politics in Karakoram in The Telegraph on 6 August 1983. This was followed by Oropolitics – A dissertation on the political overtones of mountaineering in the East-Central Karakoram 1975-82 published in the Alpine Journal of London in 1984 (p. 74). There is no evidence to show that Pakistan used the factum of these explorations or the presence of this extension in atlases to its advantage to assert any territorial claim beyond NJ 9842 between 1949 and 1983. This argument emerged in the Pakistani media only after the Indian occupation of the Saltoro Heights on 13 April 1984 and some of its proponents actually relied on Sircar’s list of explorations to make their case.42

While the erroneous extension of the CFL in maps per se did not disturb the peace of this region, the fact that expeditions were increasingly seeking permissions from Pakistan certainly reinforced the perception that it exercised some sort of de facto control over the area. Perhaps it is this sense of entitlement which gave birth to an incorrect claim line in 1983 which Pakistan sought to justify using the same distorted maps. While doing so it conveniently ignored the entire contemporaneous record to the contrary and also failed to appreciate that maps cannot be viewed in derogation of the intent expressed in the written text governing them, which in this case is the CFA. Correctly or incorrectly produced maps, especially by third parties, cannot form the basis of any territorial claim and any selective reliance placed on them by either side to justify, assert or negate any such claim is completely misplaced.

Of cartographic aggression, aberration, practicality and cosmetology

Many commentaries, particularly those emanating from India observe that Pakistan resorted to cartographic aggression to add credence to its claims to this region.43 However, this is far from the truth. It would be completely erroneous to label the appearance of the line joining NJ 9842 with the Karakoram Pass an act of cartographic aggression by Pakistan because it was neither conceived by it, nor drawn by it, nor reproduced by it, nor claimed by it till 1983. Suffice to say, that at least till 1984 this extension appears to have been only done by third parties, in complete derogation of the line visible on the primary source document. Therefore, at best, it is a cartographic aberration, which innocuously entered the discourse and was subsequently appropriated by Pakistan in 1983. In fact, Hasan Askari Rizvi fairly admits that Siachen Glacier surfaced rarely in the security discourse in Pakistan and India before 1984 with the exception of some official statements in the late 1970s and the early 1980s. Most published works including newspaper reports on the Siachen Glacier appeared after April 1984. Once India moved its troops into the glacier area, a rationale had to be articulated. Pakistan built its argument to counter India’s claim and assert that historical evidence supported Pakistan’s claim on the area. These arguments could be described as afterthoughts or ex post facto rationalizations.44

Further, till 1984, there was no dispute between India and Pakistan on the status of the region beyond NJ 984245 and neither of them had extended the Line beyond it in their own maps. Therefore, it is unlikely that anyone else would have done so with an ulterior intent or strategic objective. This can also be inferred from the fact that in most of the books where the Line has been initially extended to the State boundary, it is not even the subject matter of any discussion in the text and the maps are only being used for representational purposes to lend geographical support to the commentary. It appears that an innocuous assumption about a boundary being visually closed when represented on a map (which is normally the case), led to the CFL being erroneously extended to the State boundary in various publications.

Even practically, this artificial line appropriated by Pakistan on paper, makes little sense as a geographic boundary on the ground as it literally cuts across the Saltoro Ridge, the glaciers and the mighty peaks of the Eastern Karakoram Range before finally reaching the Karakoram Pass. On the other hand, if the CFL of 1949 were to be extended north, following the lie of the land, as per UNCIP’s demarcation guidelines that the line shall, to the greatest extent possible follow easily recognizable features on the ground46 and in accordance with internationally accepted principles of delineating boundaries in mountainous terrain along the high crests separating the watersheds, then it would nearly run along the Saltoro Ridge as it is the most predominant feature in the region constituting a natural boundary between the two sides. The only reason why the line held by the Indians has a northwestern orientation is because the Saltoro happens to be aligned as such and moving along its crest lines is the only practical way to proceed north in the region while creating a working boundary.

While many commentators, including those from Pakistan,47 realizing the futility of trying to persist with the existence of Hodgson’s Line, have started representing the LoC correctly by terminating it at NJ 9842, there are others who continue to depict it erroneously. If the LoC is terminated at NJ 9842 then Pakistan’s northeastern borders will always remain ‘open’, clearly a visual nightmare no cartographer would want in a boundary. Therefore, the continued presence of the extension of the LoC to the Karakoram Pass in some publications, while depicting Pakistan, is more for cartographic cosmetology than any cogent reason. However, instead of picking sides and showing this distortion like an international border, all commentators/authors and atlases would do well to maintain some semblance of impartiality by simply sticking with the UN version of the LoC which terminates at NJ 9842, if at all they need to show it in any map of Pakistan.

Conclusion

The origin of the Line joining NJ 9842 with the Karakoram Pass lies in the distortion of the CFL in some maps produced by third parties, contrary to the CFA. Even though the cartographic aberration started in the early 1950s, the extension of the Line to the Karakoram Pass appears to have entered the mainstream through the Penguin Atlas of 1956 and Times Atlas of 1959. Till September 1968 most of the maps published by the US Government rightly left the ceasefire line well short of the State boundary. However, pursuant to Hodgson’s directives of 18 September 1968, new maps emerged in which the CFL was extended to the Karakoram Pass in a straight line, similar to the ADIZ line of TPC-G7D of 1967. The imprimatur of the US Government on this extension was enough for commercial map makers to take cue and follow suit. Pursuant to the matter being raised by India, the US acknowledged the error and rectified the cartographic anomaly in 1987 by removing Hodgson’s Line from its maps. However, despite its deletion, many publications continue to persist with it. This extension, based entirely on conjectures and surmises, is imaginary and apart from cartographic convenience, has no legal, historical, equitable, geographical or practical foundation. Pakistan itself formally staked claim and control over the region lying to the west of this line for the first time in its protest note of 21 August 1983, nearly 34 years after the execution of the CFA. Prior to this, there is no official map of Pakistan showing this extension, and no contemporaneous record showing that Pakistan ever seriously pursued any territorial claim beyond NJ 9842 based on it.

** Amit Krishankant Paul is an independent researcher and the author of the book, Meghdoot: The Beginning of the Coldest War (Notion Press, 2022).

Email: amitkrishankantpaul@gmail.com.

MAP INDEX

Figure 1: United Nations Map 239/January 1950: One of the maps showing the ceasefire line agreed between India and Pakistan.

Source: UN Map Library

Figure 2: Jammu and Kashmir: US Map of January 1968 showing the CFL terminating well before the State boundary. (Pre Hodgson’s directive)

Source: Library of Congress, Map Collection

Figure 3: Kashmir Area: US Map of January 1970 showing the CFL extending till the Karakoram Pass (Post Hodgson’s directive)

Source: Library of Congress, Map Collection

Figure 4: Map issued by the Embassy of Pakistan in USA in 1964 showing the CFL without any extension

Source: Pakistan Affairs, Washington DC, August 14, 1964, Vol. XVII, No. 14.

Figure 5: Map of West Pakistan, Kashmir, East Punjab and Rajisthan showing International Boundaries and Cease-Fire Lines of 1947 and 1965, Ferozsons, Lahore (1965/66 and 1970/71): Map issued in Pakistan showing the CFL extending due north from NJ 9842 and not towards the Karakoram Pass

Source: Library of Congress, Map Collection

NOTES

- Agreement between Military Representatives of India and Pakistan regarding the establishment of a Cease-Fire line in the State of Jammu and Kashmir, Annexure 26, Third Interim UNCIP Report, S/1430/Add. 1 dated 9 December 1949.

- For the protest note of 21 August 1983 and the build up to Operation Meghdoot see, Lt. Gen. M.L. Chibber, “Siachen –The Untold Story”, Indian Defence Review, 5(1), Jan-March, 1990. There is no dispute on the applicability of the CFA to the region beyond NJ 9842. Lt. Gen. Jahan Dad Khan in his book, Pakistan Leadership Challenges, Oxford University Press 2001, writes at page 223 that the CFL was agreed upon and marked on the ground till Point NJ 9842. However the Karachi Agreement described the line beyond this point as thence north to the glaciers’; H. Suharwardy in ‘Siachin Glacier–Facts and Fallout; The Muslim, Islamabad, 1 May 1986 writes that the Siachin area did not witness any military action during the Indo-Pak conflicts of 1965 and 1971.As a consequence of the Simla Accord of 1972 the Cease Fire Line was renamed as the control line, but Siachin remained unaffected although some changes took place in the nearby Kargil Sector. The previous description of the line running north from PT 9842 remained intact…;General Khalid Mahmud Arif, India’s Siachin Adventure, 21-22 May 1989; The Dawn writes that the Karachi Agreement of 1949 continues to remain in force except in parts which have been modified through mutual consent; Jasjit Singh, “Siachen Glaciers: Facts and Fiction”, Strategic Analysis, October 1989 at p 703, while referring to the CFA writes, in view of the fact that this is the only agreement so far pertaining to this area, even the limited nature of the agreement becomes important.

- The fact that India pre-empted Pakistan is no longer res integra. See Jahan Dad Khan, Pakistan Leadership Challenges, Oxford University Press, 2001, 225, 226; Zulfikar A. Khalid, “The Geopolitics of the Siachen Glacier”, Asian Defence Journal, 11, 1985; Pervez Musharraf, In the Line of Fire, Simon and Schuster, 2006, pp. 68,69; Shuja Nawaz, Crossed Swords: Pakistan, Its Army and the Wars Within, Oxford University Press,2008?) p 508.

- Hasan Askari Rizvi,“Siachen Glacier Political and Geostrategic Dimensions”, in P.I. Cheema, Pakistan India Peace Process, IPRI, Islamabad, 2010, p. 81.

- Map of the Karachi Ceasefire Agreement, United Nations Security Council, General, S/1430/Add.2,12 December 1949, UN Map 239/January1950 and UN Document S/1791/Add.1 dated 27 September 1950, are some of the UN maps which show the correct alignment of the CFL.

- Some publications between 1950 and 1968 showing the CFL without the extension and terminating it well within the State Boundary: Margaret W. Fisher, Himalayan Battleground, Frederick A. Praeger, 1963;Vijay Kumar, Anglo-American Plot Against Kashmir, People’s Publishing House, 1954; Sirdar P.S. Sodhbans, Genesis of the Kashmir Problem, Deepak Publications, 1961; Lord Birdwood, Kashmir, July 1952, International Affairs; Michael Brecher, The Struggle for Kashmir, Oxford University Press, 1953, p.1; Josef Korbel, Danger in Kashmir, Princeton University Press 1954, p. 51; Alastair Lamb, The Kashmir Problem, Frederick A Praeger, 1966; O.H.K. Spate and A.T.A. Learmonth, India and Pakistan, Land, People and Economy, Methuen & Co. Ltd, London, 3rd Edition, 1967, p.1.

- See maps at pp. 40, 82.

- See Kashmir in Maps, Information and Broadcasting Division, Ministry of the Interior, Karachi, 1949; Kashmir in Maps, Public Relations Directorate, Ministry of Kashmir Affairs, Government of Pakistan, Rawalpindi, 1951 and 1955. In all these maps, the orientation of the CFL towards its end is northeastwards and nearly horizontal instead of north. However, in the Map of Jammu and Kashmir State and Gilgit Agency, Information Division, Embassy of Pakistan, Washington DC, 1963, the same line has been depicted pointing due north as per the agreed delineation pursuant to the CFA.

- Robert G. Wirsing,India, Pakistan and the Kashmir Dispute, Rupa and Co, 1995, pp 77-83.

- Letter dated 22 August 1994 written by Schwartzberg to Wilkes, accessed by the author.

- Letter dated 30 March 1995 by Pountain to Schwartzberg, accessed by the author.

- For the map by Bill Perkins, refer to the Library of Congress (LC) map collection. For TPC G7D: Perry Castaneda Library (PCL) Maps Collection, University of Texas at Austin.

- State Department/CIA Map of Jammu and Kashmir before Hodgson’s directive of 1968: Source: Library of Congress map collection.

- Freddie Wilkinson, “A Line in the Mountains”, National Geographic, March 2021, p 86.

- Airgram A-415, A-1245 and A-418 declassified by the State Department.

- Freddie Wilkison, no. 14.

- State Department/CIA map of Jammu and Kashmir post Hodgson’s Directive of 1968 Source: Library of Congress map collection.

- State Department map of Pakistan 1973 Source: PCL Maps.

- ONC G-7: Refer PCL Maps.

- Refer PCL Maps.

- Refer PCL Maps.

- Jaishankar’s letter accessed by the author.

- Demko’s letter accessed by the author.

- Demko’s directive accessed by the author.

- In late 1988, two maps were produced almost simultaneously. In the map, India-Pakistan Border: Kashmir Area, the Siachen conflict zone was shown as an inverted triangle in a colour tone different from what was being used for both India and Pakistan with the words ‘Indian occupied since 1983’ clearly written inside. The Ceasefire Line was terminated at NJ 9842, and the words ‘undefined boundary’ were written in place of the extension between NJ 9842 and the Karakoram Pass. However, in the other map China-India Border: Western Sector, no such triangle was shown. Even though the CFL was terminated at NJ 9842, the area to the west of the imaginary line joining NJ 9842 with Karakoram Pass was shown in the same colour tone as Pakistan with the words ‘undefined boundary’ written in place of the imaginary line, once again creating an impression that the region fell on the Pakistani controlled side. Refer PCL Maps.

- Letter accessed by the author.

- Ibid.

- G. Verghese, Siachen Follies, CPR Occasional Paper No. 20, May 2012, pp. 9-16.

- Wood’s letter to Schwartzberg, accessed by the author

- Ishtiaq Ahmed, Siachen:“A By-Product of the Kashmir Dispute and a Catalyst for its Resolution”, Pakistan Journal of History & Culture, 27(2), 2006, p. 93.

- Robert G. Wirsing, “The Siachen Glacier Dispute-I: The Territorial Dimension”, Strategic Studies, Autumn 1986, 10 (1), p. 61.

- Refer Library of Congress map collection.

- Pakistan Affairs, 17 (14), 14 August 1964, Washington DC. See also Vol. 17, 1 June, 1964, which gives a map of Jammu and Kashmir showing the CFL exactly as per the CFA and without any extension to the Karakoram Pass.

- Map of West Pakistan, Kashmir, East Punjab and Rajisthan showing International Boundaries and Cease-Fire Lines of 1947 and 1965, Ferozsons, Lahore, 1966 and 1971.

- See also map at page 361 of Razvi’s book which does not show any line joining the Karakoram Pass with NJ 9842; Nasim Zehra in her book From Kargil to the Coup, Sang-E-Meel Publications, Lahore(2018), p. 34, admits that Pakistan did not raise the matter adequately at the international or bilateral levels..

- For example, see Postage stamp: 14 October, Pakistan, 1955, Maps of Pakistan in Pakistan Geographical Review 1955, Panjab University, Lahore, p.3 and Pakistan, Sixth Year, 1953, Pakistan Publications, Ferozsons, Karachi, 1953in which Jammu and Kashmir is shown distinct from Pakistan and no CFL is shown in the map. See also postage stamps: 23 March Pakistan, 1960; Shahrah-E-Pakistan, 1974; Anniversary of independence, 1982 and Quami Parcham, March 1998 where the state of J&K is shown in colours distinct from the rest of Pakistan and no CFL/LOC is shown. For a commentary on postage stamps refer to Krishna Kant, “Pakistan’s philatelic brazenness, waging a proxy war against India one stamp at a time since 1954” at opindia.com (11 November 2018)

- Khalid Mahmud Arif (Retd), in “India’s Siachen adventure”, Dawn, Karachi, 21-22 May 1989, while commenting on India’s occupation of the Saltoro Heights writes: such an act also violates the Karachi Agreement of 1949 which continues to remain in force except in parts which have been modified through mutual consent. By inducting her military forces in the Siachen glacier India has violated the Simla Agreement and the Karachi Agreement.’Thereafter in his book Working with Zia, Oxford University Press, 1995, p 223, he writes ‘In early 1984 in blatant violation of the Cease Fire Agreement 1949, the Line of Control Agreement 1972 (negotiated after the 1971 war), and Simla Agreement 1972, Indian troops infiltrated into the Siachen glacier area and occupied some high passes’.

- Riaz Mohammad Khan, Conflict Resolution and Crisis Management, Stimson Center, 2011, p.78.

- Foreign Relations of the United States 1964-1968, South Asia.

- Amit K. Paul, The Siachen Story: The Inadvertent Role of Two German Explorers in Starting the Race to the World’s Highest Battlefield, Observer Research Foundation, 24 April 2024,

- Amit K. Paul, “The first GSI Survey of Siachen”, The Hindu, 13 July 2023.

- Zulfikar Ali Khalid, “Geopolitics of the Siachen Glacier”, Asian Defence Journal, 11(1985)

- See for example, Dinakar Peri, “Siachen: 40 years of Operation Meghdoot”, The Hindu, 15 April 2024.

- Hasan Askari Rizvi, 4, p 81.

- In an article in Dawn (30 June 1986), “Siachen: The Glacier won’t move”, Brig (Retd.) A.R. Siddiqui writes: “Even between India and Pakistan, through their three wars (1947-48, 1965, 1971) Siachen did not even remotely figure as a controversial point. In fact except for personnel of the military operations branch and mountaineers, most of us had not even been aware of its existence...”

- 21, S/AC.12/195,2 May, 1949 in UNSC document S/1430/Add.1 dated 9th December 1949 being the Annexure to the Third Interim Report of UNCIP.

- Shuja Nawaz, Crossed Swords, Oxford University Press, 2008, p 4; A R Suharwardy, Tragedy in Kashmir, 1983, Wajidalis, Lahore, Pakistan; Lt. Gen Mehmood, “Siachin Dispute and Status of Northern areas”, Asian Defence Journal, 19 (5-6), 1993; Pervez Musharraf, In the Line of Fire, Simon and Schuster, 2006, p.1.

Comments